Summaries by Nathan Elliott. Formatting and editing by Madeline Rizzo

| On Demand | Day One | Day Two | Day Three |

|---|

Civitas Networks for Health® is a national collaborative comprised of member organizations working to use health information exchange, health data, and multi-stakeholder, cross-sector approaches to improve health.

Civitas Networks for Health® is a national collaborative comprised of member organizations working to use health information exchange, health data, and multi-stakeholder, cross-sector approaches to improve health.

We’re in San Antonio this year for the Civitas Networks for Health 2022 Annual Conference. Join us over the upcoming days as we recap selected sessions from this year’s events! In this installment, we recap some of our favorite Day One sessions.

Welcome

- Date: Monday, August 22, 2022

- Presenters:

- Lisa Bari, MBA, MPH, CEO, Civitas Networks for Health

- Scott Stuewe, President and CEO, DirectTrust

- Overview: Civitas Networks for Health CEO, Lisa Bari, and DirectTrust President and CEO, Scott Stuewe, open the first full day of the conference, delivering two key announcements and a call to action for attendees to start finding more common ground.

Civitas’ Lisa Bari and DirectTrust’s Scott Stuewe welcomed this year’s attendees to the conference (600 in person and 200 virtually) and announced the following:

- Civitas has signed a letter of intent with Health Level Seven® International (HL7®) and the Gravity Project (HL7 FHIR Accelerator focused on Social Determinants of Health data) to collaborate on implementation and dissemination efforts.

- The Patient Centered Data Home® Governance Council and Civitas have named Velatura Public Benefit Corporation as the national Solution Partner for PCDH.

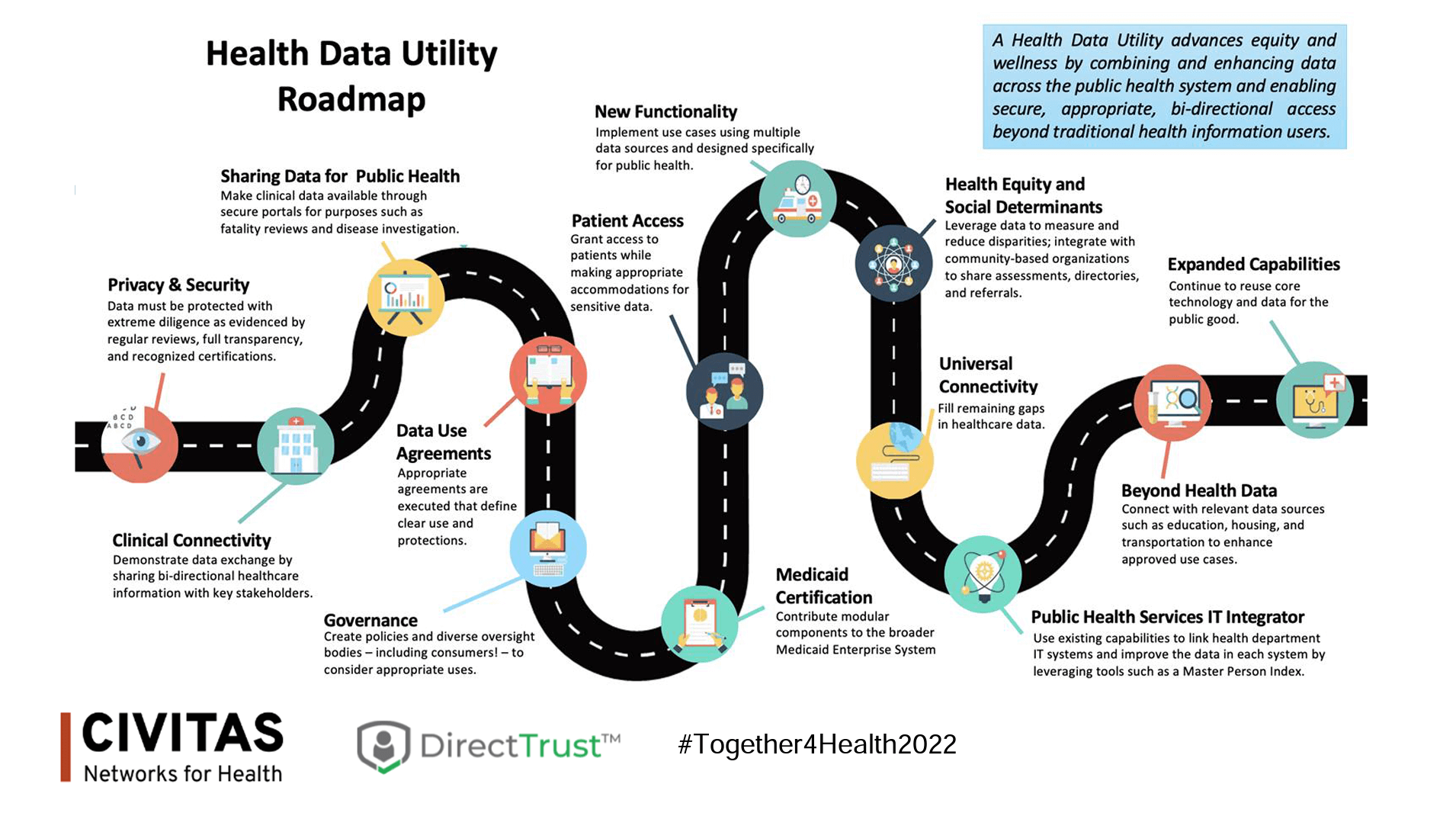

In Civitas’ inaugural year, Bari called attention to some important changes in how the organization’s membership is evolving. Most notably, what has been commonly referred to as health information exchanges (HIEs), regional health improvement collaboratives (RHICs), quality improvement organizations (QIOs), and all-payer claims databases (APCDs) are expanding their roles and blurring lines distinguishing one from another by traditional definitions. This role expansion is perhaps a demonstration of the shift from filling specific niche needs to functioning more as what Bari considers public-private “health data utilities” (HDUs). Look for more references to members functioning as HDUs going forward.

Bari talked about the focus of this year’s conference in partnership with DirectTrust: Health Equity. Trust, social determinants of health (SDOH) data, interoperability, and community are key concepts in advancing health equity, and we expect to hear much more about these in this week’s conference sessions.

Stuewe talked about DirectTrust’s evolution over the past ten years and increasing use among major vendors and solution providers (sessions this week will highlight examples of Direct secure messaging solutions). Conferences like this are where important conversations happen that spawn new collaborations and meaningful advancements in this sector. As one example, Stuewe’s hallway conversations with Lisa Bari at the last SHIEC conference led to this year’s combined Civitas/DirectTrust conference.

According to Stuewe, it is now time for organizations to reach beyond their normal networks and talk about creative partnerships. HIEs, for example, should consider talking to their HISPs to discuss mutual needs and opportunities. There are many more places to start conversations too, as will be featured this week. A key theme in this year’s conference is to bring more people to the table to explore how to leverage the technology that we already have to do more good for more people—especially those struggling to enjoy equitable experiences.

As Bari put it, “We are critical infrastructure for health equity. It’s time to build.”

Moving Upstream: How to Seize This Momentum to Transform the Social and Structural Drivers of Health Equity in Our Communities

- Date: Monday, August 22, 2022

- Presenter: Rishi Manchanda, M.D., M.P.H., CEO, HealthBegins

- Overview: Rishi Manchanda, MD, MPH, explains the core tenets of what health equity means, as well as discusses threats to equitable treatment and steps we can all take to build health equity into our careers and lives.

Dr. Rishi Manchanda, a primary care physician and public health expert, walked audience members through a brief history of his family’s experience with the “Partition” as India became a new nation a generation ago. It was a time of tragedy and mass disruption mixed with excitement about freedom for a new future.

Manchanda’s family faced discrimination consistently in subsequent decades, even after coming to the United States, often from what he described as “structural violence.” Structural violence entails embedded practices or policies in political and economic organizations worldwide that cause injury to people (usually not those responsible for perpetuating them).

We often hear about the Triple Aim, sometimes the Quadruple Aim, but Manchanda and his organization, HealthBegins, focus on the “Quintuple Aim”:

- Costs

- Patient Experience

- Provider Experience

- Outcomes

- Equity

From a cost perspective alone (according to Kaiser Family Foundation), health disparities amount to an estimated $93 billion in excess medical care costs and $42 billion in lost productivity per year. Of course, the financial costs are less important than the human costs of failing our community members.

The concept of “structural violence” means persistent barriers to achieving equity, which is really about treating everyone fairly. The exploitation of those with less power and fewer resources, marginalization/exclusion of people and entire communities from access to even basic services and opportunities, and the fragmentation of communities and disruption of resource sharing can all result from structural violence.

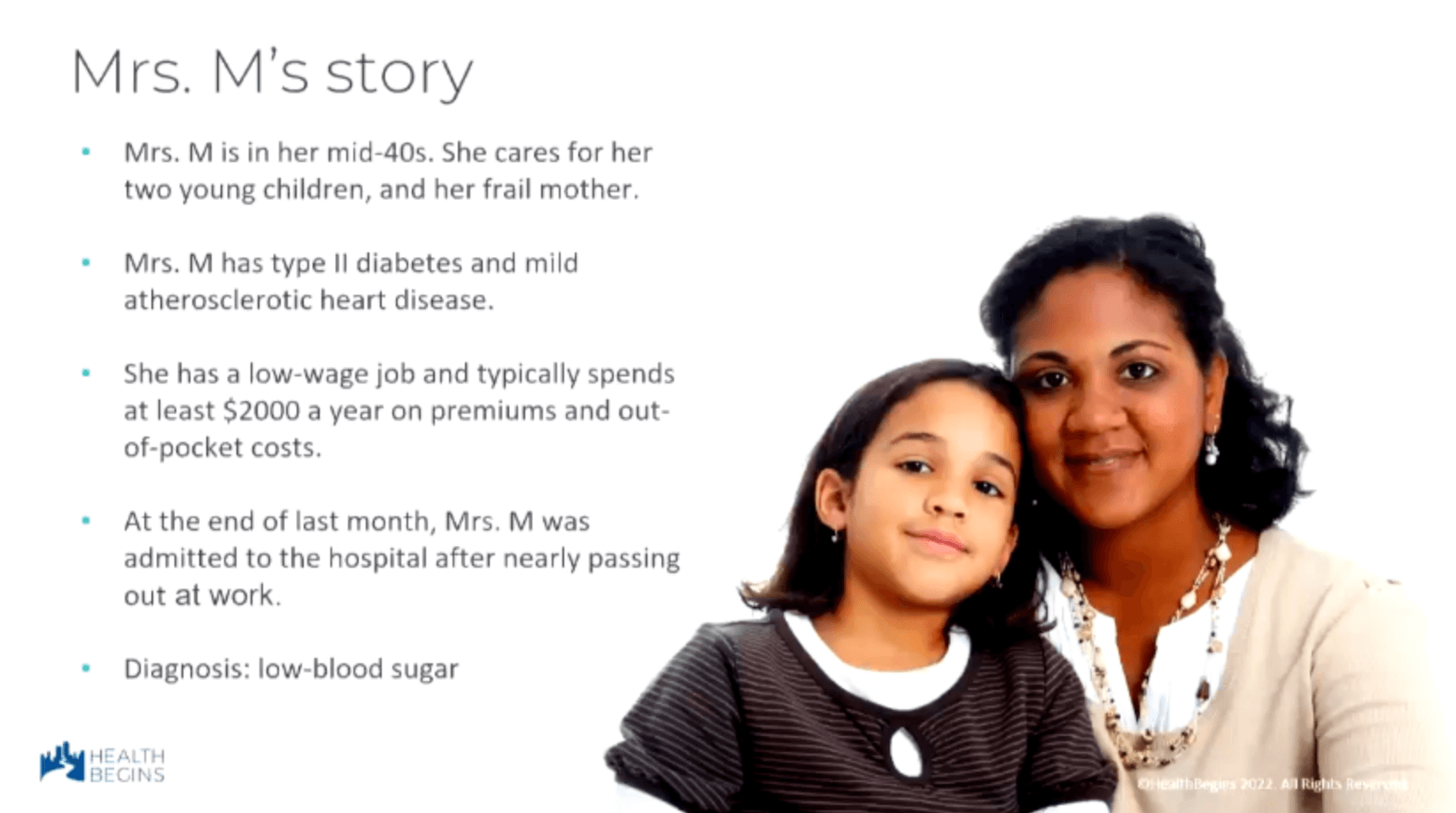

Manchanda told the story of a fictional woman to help illustrate what all of this means at an individual level. Mrs. M, a single mother of two young children in her mid-forties who self-identifies as biracial (Black and Latina) cares for her frail mother in her home. She has also been dealing with Type II diabetes and mild atherosclerotic heart disease. She has a low-wage job and typically spends at least $2,000 per year on premiums and out-of-pocket expenses.

At the end of last month, Mrs. M was admitted to the hospital after nearly passing out at work (diagnosis: low blood sugar). If we look at other factors in Mrs. M’s life, Manchanda explained, we can find that she and her family experience food insecurity. This insecurity is compounded by the fact that they live in a “food desert” (an urban area where it is often difficult to find and purchase fresh, healthy food). The food desert exists because of “supermarket redlining,” a form of structural discrimination or even racism, which is a form of structural violence. To provide context here, Manchanda presented a slide that depicted the layers of racism:

- Structural – “The totality of ways in which multiple systems and institutions interact to assert racist policies, practices, and beliefs about people in a racialized group.”

- Institutionalized – “Discriminatory treatment, unfair policies and practices, and inequitable opportunities and impacts within organizations and institutions based on race.”

- Interpersonal – “The expression of racism between individuals, through discrimination, bias, harassment, or slurs.”

- Internalized – “Exists within individuals; the acceptance by members of stigmatized races of negative messages about their own abilities and intrinsic worth.”

There is more to know about Mrs. M. Recently, her home was foreclosed. She moved her family to a rental unit and has been unable to pay her medical bill from the hospital stay. The hospital sued, her wages were garnished, and she eventually lost her job. Now, she cannot find affordable healthy food and still has to take care of her children and frail mother. In order to care for her family and still take her diabetes medications, she decides to skip meals. These circumstances are a lot of weight and stress to bear, but people feel these kinds of pressures daily.

There is more to know about Mrs. M. Recently, her home was foreclosed. She moved her family to a rental unit and has been unable to pay her medical bill from the hospital stay. The hospital sued, her wages were garnished, and she eventually lost her job. Now, she cannot find affordable healthy food and still has to take care of her children and frail mother. In order to care for her family and still take her diabetes medications, she decides to skip meals. These circumstances are a lot of weight and stress to bear, but people feel these kinds of pressures daily.

If we look at a broader level, laws and policies can directly influence lifestyles like that of Mrs. M and her family. Between 2010 and 2013, researchers identified more than 843 state laws that disproportionately discriminated against marginalized racial and ethnic groups. We should consider the effect of these policies in our health equity response plans. Similarly, health disparities are often linked to location. The southern states of the U.S. tend to show the greatest unmet needs. There are certainly individual communities across the country where needs are highest.

Manchanda offered a few takeaways from a report from the Brookings Institution:

”Place affects an individual’s ability to access almost every dimension of opportunity, including education, health, the internet, jobs, and quality housing.”

”Regardless of which specific measures are used to define [high-need] communities, poor people of color are far more likely to live in them than poor whites are.”

”There are poor people of every race. But only poor people of color are systematically confined in poor places.”

”Public policy created this pattern of residential segregation. It will take policy reform and a proactive, place-based approach to mitigate the harm caused by these policies.”

Why is this so? Manchanda cited an article in the New England Journal of Medicine titled, “Lack of equity in policy design perpetuates structural inequities & harm.” A few excerpts:

”By more frequently penalizing institutions caring for high proportions of Black adults, many of these programs have also unintentionally perpetuated structural racism.”

”Value-based payment initiatives have failed to advance health equity in large part because equity wasn’t prioritized during their design and implementation.”

The point here is that until we start making health equity explicit in our policy language at every level, we’re going to continue to miss groups of people and perpetuate inequities in one form or another. To make meaningful change, we need to address issues at multiple levels:

- Social needs at an individual level.

- Example: Food insecurity

- Social Determinants of Health at a community level.

- Example: Food deserts

- Structural Determinants of Health Equity at a societal level.

- Example: Supermarket redlining

During this week’s conference, attendees will hear more about how data will be essential to supporting change at each of these levels. We will hear about how a lack of useful data leads to effectively “erasing” people from existence, the kinds of data that payers are still struggling to capture, how social services organizations have been deprioritized, and about how biases continue to skew both data and paths forward.

Manchanda sees a great opportunity for HIEs and other organizations in this space to make and facilitate important strides forward. These organizations can inform communities/policymakers about not only surfacing where needs are and what those needs are but also where interventions, programs, and policies are making a difference.

Developed and led by Civitas Networks for Health, policymakers are now hearing about Health Data Utilities (HDUs) and their potential for helping to address unmet and unidentified needs (inequities). HIEs and related organizations are increasingly viewed by the government as critical infrastructure for health equity.

As one example, the CDC’s Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) Public Health Use Case Workgroup recently identified use cases that focus on the functionality and interoperability required to allow an end-user to send and exchange coded SDOH-related data.

However, there’s more that can be done outside of government to help lead us in the right direction. From a healthcare industry perspective, Manchanda cited “At Toolkit for Centering Racial Equity Throughout Data Integration” from Actionable Intelligence for Social Policy at the University of Pennsylvania. We should prioritize explicit adjustments for, and embed health equity considerations into, our use of data. With these adjustments, we can tell the stories that need to be told to help make change. Consider health equity during:

- Planning

- Data collection

- Data access

- In algorithms and use of statistical tools

- In data analysis

- In reporting and dissemination

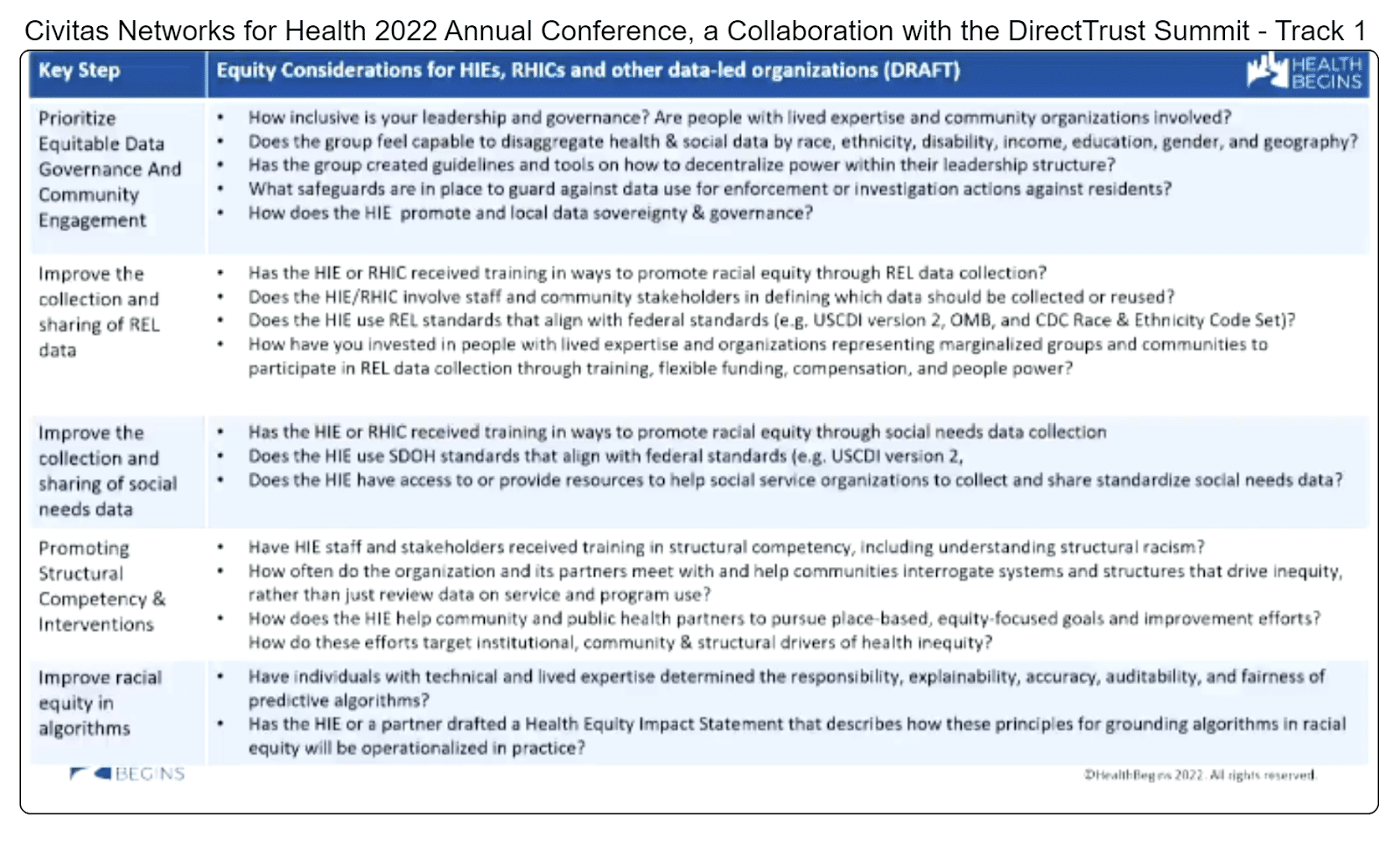

Manchanda also offered his own list of health equity considerations for HIEs, RHICs, and other data-led organizations:

Organizations also have, or have had, structured programs through which to help lead change. Manchanda listed the following such programs and opportunities for involvement and encouraged attendees to consider similar future opportunities:

Organizations also have, or have had, structured programs through which to help lead change. Manchanda listed the following such programs and opportunities for involvement and encouraged attendees to consider similar future opportunities:

- Accountable Communities for Health

- Purpose Built Communities

- Communities of Opportunity

- Strong, Prosperous, and Resilient Communities Challenge (SPARCC)

- Modernized Anit-Racist Data Ecosystems (MADE) for Health Justice (deadlines due August 31, 2022)

- NASEM Committee on the Review of Federal Policies that Contribute to Racial and Ethnical Inequities (tasked by Office of Minority Health) (oral comment on September 9, 2022; written comments due by September 30, 2022)

In terms of steps forward, Manchanda advises putting race, ethnicity, language, and other demographic data to use to demonstrate gaps in services and outcomes by comparing groups in your community. Tell those stories. In addition, start to structure your plans in ways that explicitly call attention to health equity. Manchanda provided the following example:

For a QI project focused on improving childhood immunizations among families by addressing unmet social needs, a team would first collect and review REL (race, ethnicity, language) data to identify differences in outcomes among two or more groups.

Then, the team could set appropriate QI goals:

- Achieve a 20% increase from baseline in childhood immunizations among all families, AND

- Eliminate inequities in childhood immunizations between the racial group with the lowest rates and a comparator group

If equity is not called out as a specific goal, we will most likely continue perpetuating the problem.

Manchanda took questions from the audience, including the following examples:

Q: Providers are already pretty burned out. These are great concepts, but it’s yet another concept to try to implement. How can we do this successfully?

Manchanda responded by addressing some common responses to adding health or health data equity to the conversation with providers. For example, we might hear, “I treat everyone the same.” This response shows a defensive perspective at an “interpersonal” level, not an attempt or willingness to address the problem at one of the other layers, such as structural. Similarly, how does the provider know that they treat everyone the same without seeing the data? Does their choice of words affect their patients differently?

Sometimes, the answer for providers is recognizing the moral injury that occurs when they are unaware of specific resources that might benefit their patients or recognizing when those resources are not available in their community. In these cases, it is important to understand these pain points, talk openly about them, and begin to work on community-based solutions.

Q: This audience is mostly implementers, not activists. What can we do?

Regardless of the specific nature of your professional work in this space, we are all leaders. We need leadership and courage to shift how we interact on a daily basis. Equity should be visible in conversations, questions, and solutions. As we do this more, we will see more effectiveness and better outcomes.

Manchanda is looking forward to the Civitas membership helping to share and design the roadmap to health equity.

For more information about Manchanda’s work and resources, visit healthbegins.org or find him on social media.

Empowering Patients with Data to Improve Health Equity

- Date: Monday, August 22, 2022

- Presenters:

- Deven McGraw, MPH, JD, Lead, Data Stewardship and Data Sharing, Invitae

- Dan Porreca, Executive Director, HEALTHeLINK

- Craig Behm, MBA, Executive Director, Chesapeake Regional Information System for Our Patients (CRISP)

- Grace Cordovano, PhD, BCPA, Board Certified Patient Advocate, Enlightening Results

- Sara Abrams, MPH, VP, Data Analytics and Quality Assurance, Rochester RHIO

- Overview: In this presentation, the presenters discuss simplifying patient access to HIE (or HDU) data, which is framed by the urgency of Grace Cordovano’s experiences on the front lines of serving patients with high-severity needs.

Grace Cordovano has spent her career working with the most underserved and vulnerable populations in her community in New Jersey. She works at the crossroads of catastrophic diagnoses and end-of-life care.

We are often told that we are all patients or will be, but Cordovano wanted the audience to think about the emotional/life-changing differences between being a patient at a doctor’s office for a wellness check or in the ED for, say, a sprained ankle, versus the experience of being a patient told that their cancer is no longer responding to treatment. There are important differences between routine care and, for example, a parent going from specialist to specialist trying to find a diagnosis and treatment for a child’s rare and possibly degenerative disease. In other scenarios, some patients might be making a choice about diet and exercise, while others are choosing how to die.

Cordovano thinks about patients in 5 groups:

- Healthy/Proactive Wellness Seeker

- Acute Episode

- Chronic Illness(es)

- Life-Altering Diagnosis/Rare Diseases

- End of Life & Death Care

She considers the first two “Acts of Consumerism,” while the remaining three are “Acts of Survival.” These levels of patient experience should also be considered when we think about SDOH. As we move through the severity levels, SDOH factors can have increasingly negative effects.

This premise can all begin to sound a bit depressing, but Cordvano is excited about the future of HIEs and removing barriers. She sees improved access paying off for patients who have greater access to their information and community resources, including finding or participating in trials, being able to appeal a denial, and navigating information and tools more easily, such as scheduling appointments with less burden on patients and family caregivers.

Cordovano shared an example of a patient experiencing debilitating symptoms and was losing her ability to function in day-to-day life. She might be able to apply for services related to rare diseases, but there are many requirements, and she needs information in an easy-to-use format. In a situation where the person is already having many symptoms, the onus of putting everything together to apply can be exhausting and frustrating, if not altogether defeating.

We often talk about our technical capacity and capabilities to solve problems, but we haven’t been talking enough about patient administrative burden. This burden is what patients have to go through to get what they need. With so many steps, manually entered and repeated data points, and an overwhelming number of tools with overlapping and partial solutions, how can we expect anyone, let alone tired and fatigued patients, to get anything done?

We often talk about our technical capacity and capabilities to solve problems, but we haven’t been talking enough about patient administrative burden. This burden is what patients have to go through to get what they need. With so many steps, manually entered and repeated data points, and an overwhelming number of tools with overlapping and partial solutions, how can we expect anyone, let alone tired and fatigued patients, to get anything done?

Workflows at even the best organizations are still frequently paper-based. Fax machines are still in use. Images are still burned onto CDs. If a patient doesn’t own a fax machine but is able to get to a commercial service that offers such, it can cost $2 per page, and what if it doesn’t go through? This process can be absolutely overwhelming.

Patients and their caregivers want and need access to health information, resources, and tools to help patients live their best lives. In Cordovano’s view, we really have no excuse for this in a post-COVID world. We found better ways to do many things in a short period of time. How can we put some of that learning to use to reduce the suffering that is still happening every day?

For some patients, total recovery or optimal health might not be possible. But, we can at least keep pushing forward to ease suffering.

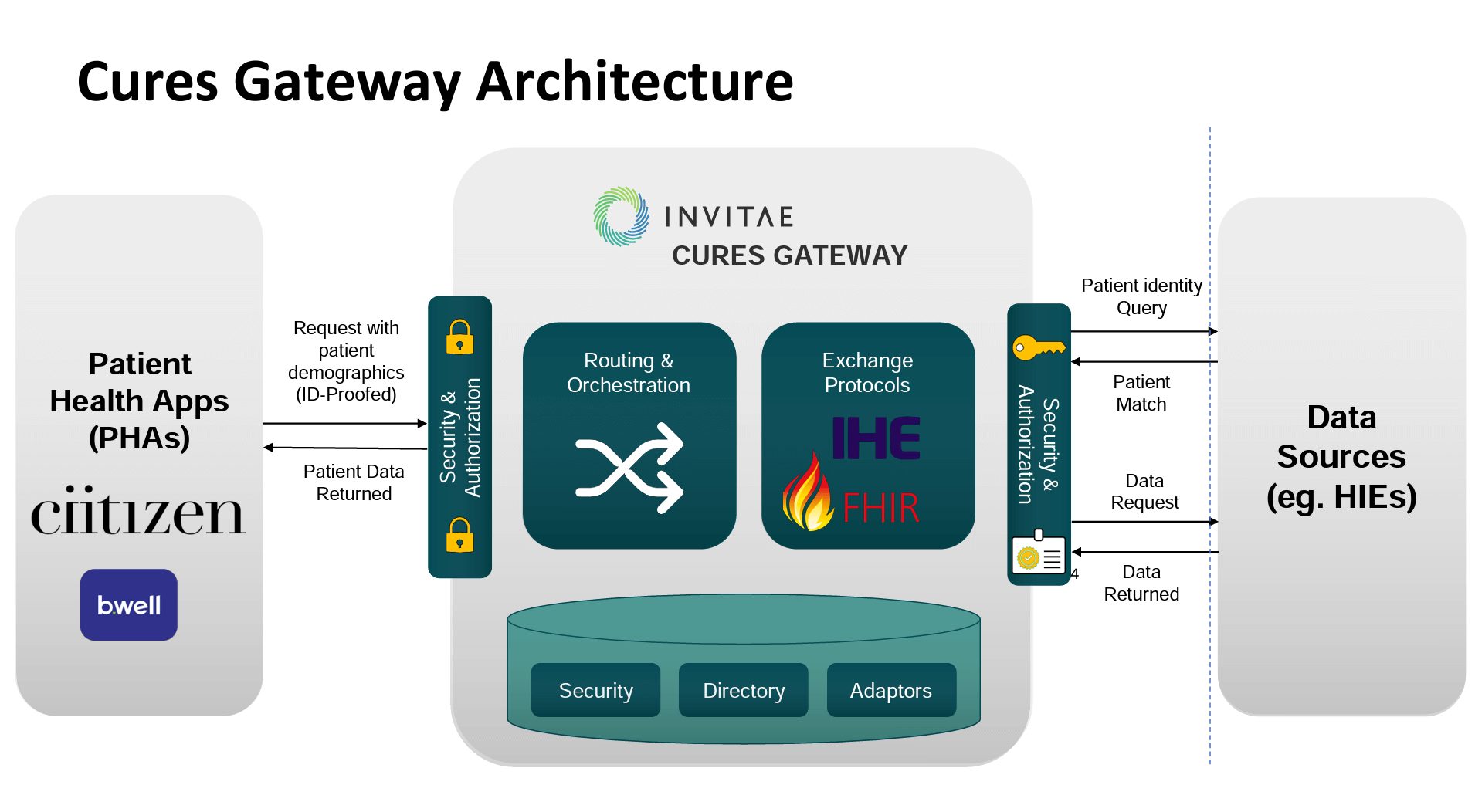

Deven McGraw presented Ciitizen’s technology solution for combining patient information and simplifying the healthcare navigation experience for patients. Their story began with cancer patients most in need, where time was not always on their side. These patients needed deeper data faster than most other patients. Often, they had to deal with multiple patient portals or medical record requests, which could take days.

Ciitizen believed that they could help fill gaps to support HIEs in serving patients with better information, going beyond the original focus on the cancer patient community. The company is now offering “Cures Gateway,” a new solution for HIEs that enables patients, in a self-directed manner, to obtain their medical records quickly and in a useful format. Some key points from McGraw about the Cures Gateway include that it:

- Leverages existing data exchange models (i.e., HIE and FHIR) to deliver patients their medical records

- Provides “identity proofing” (identify verification) of patients requesting their records

- Is simple and easy to use

- Allows patients to receive records in their PHA, in a human-readable PDF, or use a free Personal Health Record (PHR) to hold and view their records

For now, Ciitizen is offering this service at no cost to early adopters and patients.

The presentation then moved to an overview of Rochester RHIO’s partnership with Ciitizen for the Cures Gateway solution.

In 2020, Rochester RHIO joined over 170 organizations in signing and supporting a Racism/Health Crisis Declaration. The organization was committed to improving the quality of HIE data related to race, ethnicity, and gender, emphasizing building diversity in governance and its workforce. They wanted to focus on opportunities that address systemic change, advocacy, and leadership development in the community.

Today, Rochester RHIO is in the process of piloting Cures Gateway in collaboration with Northstar Network’s 2022 Healthcare Business Academy Fellowship Program. They seek to:

- Include community leaders representing organizations across the healthcare ecosystem in the Greater Rochester region

- Collaborate with key stakeholders who serve patients and communities who are disadvantaged by inequitable systems

- Ensure Cures Gateway works for ALL patients, not only “default users”

The pilot will, among other work, involve fellows working directly with staff at FQHCs to train them on how Cures Gateway works. One pilot site is in an urban area with a large black population. The other is in a rural area with a large migrant farm worker population. In both cases, there is generally low health literacy, but for different reasons. The focus for fellows is to help operationalize the use of the technology and improve the chances of successful adoption.

According to Sara Abrams from Rochester RHIO, an HIE’s role is to empower organizations and patients with data while also helping partners who can take the next step in advancing effectiveness. Rochester RHIO wants to ensure that they are able to both reduce patient administrative burden and improve outcomes.

CRISP’s Craig Brehm explained that as we move to a future with Health Data Utilities, patient access to their data is an essential need. While CRISP anticipates numerous benefits to patients with direct access to their information, Behm noted that HDUs should also think about the following.

Direct patient access to information leads to:

- Increased transparency, which builds confidence in the HDU

- More opportunities to find and fix potential data quality issues for everyone’s benefit, including an HDU’s more traditional information-sharing partners

- New stakeholders gaining direct value from the HDU

- New use case possibilities, such as updating demographics across systems and controlling consent

Dan Porreca spoke briefly about HEALTHeLINK’s presence as the RHIC for western New York. He noted that 40% of phone calls that his organization receives are requests from patients related to their data and that the majority of inquiries on their Infoline (website comment session) are patients asking about access.

We tend to think about HIEs in the context of payers, providers, hospitals, public health, and now community-based organizations and social services agencies, but we need to keep individual patient access to HIE or HDU data in front of us.

The presenters fielded a variety of questions from the audience and generally provided answers that kept with the theme that HIEs or HDUs are positioned to be conveners and facilitators for the better use of data, which should include helping stakeholders visualize, understand, and reflect on which programs, efforts, or technologies are working and how they can be improved. There are no easy answers to “who pays for” all of the advances and services, but the presenters appeared optimistic that continuing to engage in conversations with the community and public stakeholders about where the data leads us will help find sustainability.

The presenters fielded a variety of questions from the audience and generally provided answers that kept with the theme that HIEs or HDUs are positioned to be conveners and facilitators for the better use of data, which should include helping stakeholders visualize, understand, and reflect on which programs, efforts, or technologies are working and how they can be improved. There are no easy answers to “who pays for” all of the advances and services, but the presenters appeared optimistic that continuing to engage in conversations with the community and public stakeholders about where the data leads us will help find sustainability.

Cordovano shared excitement about these developments and is eager to see the results. As we introduce new technologies, we should also consider the need for, and role of, what she calls “digital health sherpas,” navigators for a digital health experience. In all the forms that health equity work is likely to take, we need to continue to remind ourselves that the focus should be on bundling and sharing information in ways that reduce burdens on the people who need to use it.

Achieving Health Equity Starts with Data

- Date: Monday, August 22, 2022

- Presenters:

- Cara James, Ph.D., President and CEO, Grantmakers In Health

- Dora Hughes, M.D, M.P.H., Chief Medical Officer, CMS Innovation Center

- Lisa Bari, MBA, MPH, CEO, Civitas Networks for Health

- Overview: Lisa Bari, CIVITAS Networks for Health CEO, leads Grantmaker’s Cara James and Innovation Center’s Dora Hughes through a discussion about how health equity data and its uses are viewed at the Federal level. The presenters also discuss how the tolerance for less than perfect data affects progress in equitable delivery of care in the U.S.

Civitas Networks for Health CEO Lisa Bari spoke with Cara James from Grantmakers in Health and Dora Hughes from the CMS Innovation Center. James has spent two decades working on health equity and completed a PhD in medical sociology. Hughes has worked on minority legislation and as a health policy advisor under Obama.

For both, SDOH and data collection have always been part of the discussion. However, even with all of the years of work, there continue to be opportunities for improvement. As recently as during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a struggle to produce fully accurate reports from sources like Medicaid because all states and territories collect data differently. While people talk about the importance of factors like income on access to health and services, this information is not collected in a way or in places where people can use it for good. There also still isn’t a consensus on term definitions. The federal government, for example, has at least 65 ways that government agencies measure “rural.” In another example, HUD and the VA ask different questions about similar aspects of a person’s life, such as housing. For example, “do you have a place to stay tonight?” versus whether the person is dealing with rodent infestations or air quality problems.

Depending on what people and organizations need, there are still gaps. James stressed that we need to continue working to close those gaps and think proactively about types of data that could be worth collecting and how data can be collected in standard ways.

She also stressed that we need to continue to work on differences between what local and state entities feel that they need to collect (and how to collect it) and what we ultimately will need at a national level. Tailored data is certainly a necessity, but local adaptations, colloquialisms, or biases can mean data not making sense at a national or regional level. Such differences are further compounded by state and local organizations needing to rely on sub-par technologies due to budget constraints. In James’ view, we are not even meeting “the floor” in some cases.

She also stressed that we need to continue to work on differences between what local and state entities feel that they need to collect (and how to collect it) and what we ultimately will need at a national level. Tailored data is certainly a necessity, but local adaptations, colloquialisms, or biases can mean data not making sense at a national or regional level. Such differences are further compounded by state and local organizations needing to rely on sub-par technologies due to budget constraints. In James’ view, we are not even meeting “the floor” in some cases.

Hughes believes that the federal government must lead the way in defining the key pieces of information that will be needed to cut across local and state variations. She explained that we are starting to see the federal government renew its interest in helping in this way. There tend to be roughly 10-year cycles in heightened federal activity associated with legislation tied to standards. In order not to miss this window and wait another ten years, the time is now to get involved and help to guide legislation to establish a common language, priorities, and incentives.

The panel largely agreed that participation and involvement are essential. This participation could be in the form of Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI, or “Innovation Center”) program participation or, more broadly, contributing to public comments and advocacy where appropriate for a given individual or organization. Federal initiatives will need a higher level of participation diversity to avoid missing or continuing to under-prioritize populations in need.

James commented that CMMI models are often pilots and making them sustainable with associated funding has been a challenge. Hughes stated that the Innovation Center is working to address these challenges and noted that, unfortunately, the Innovation Center did not always prioritize health equity, and it is difficult to assess what the overall impact of that might be over the years. Thankfully, change is happening now as the Innovation Center and its models adapt over time.

Part of that adaptation might be rethinking costs as a central driver in determining outcomes. As James put it, measuring health equity should not always be in dollars. Perhaps low cost means populations are not getting what they need. There needs to be measuring programs and outcomes in ways that demonstrate the value to patients’ well-being.

Hughes talked about Accountable Health Communities as an example of looking beyond pure costs. The model launched in 2015-2016 to help patients with social needs. Outcome data showed that clinicians could begin to capture SDOH data, but there was more need than providers expected. Overall, they saw a 9% reduction in the use of the ED for those with social needs addressed. The Innovation Center is now building on those learnings.

Integrated Care for Kids is another example. This model demonstrated a greater understanding of social needs on outcomes, health, and longevity. In Hughes’ opinion, if we had not gotten started (even if not comprehensive), we would be missing out and not building the foundation for progress.

Bari then asked the panelists about private sector funding.

Grantmakers for Health works with many organizations across the U.S., especially foundations. One of the struggles has been defining what really defines health equity and its many factors. Part of what is discussed in the private sector, according to James, is the need for policies and legislation that remove barriers and the threat of penalties for data collection and sharing, such as between providers, schools, and agencies.

Grantmakers for Health works with many organizations across the U.S., especially foundations. One of the struggles has been defining what really defines health equity and its many factors. Part of what is discussed in the private sector, according to James, is the need for policies and legislation that remove barriers and the threat of penalties for data collection and sharing, such as between providers, schools, and agencies.

One of the key ideas mentioned in this panel is the need to stop waiting for data to be perfect. The speakers felt that health equity data seems to be held to a higher standard and cannot be used if incomplete. A thought for the audience: The more we use it, the more people will work on fixing it. We really need to start using the data that we have today, report on it, and engage those who are supplying it.

Hughes mentioned that from the Innovation Center’s perspective, there is concern that after a model ends, its data simply goes away and is lost. This data could really be used for analysis and is an opportunity to work on going forward.

The panelists responded to a few questions from the audience to close the session. The prevailing theme was that now is the time to engage and charge ahead with using the data we have. The speakers stressed that we should continue to make data better and look for ways to bring everyone up to the same standard of care and have the same opportunities to enjoy the best care and services that this country has to offer. Whatever your role and professional circle, you can contribute your voice. Reach out to foundations, grantmaking entities, government agencies, and even the Innovation Center directly. Put your ideas and feedback out there for everyone’s benefit.

IIS and HIE Integrations to Advance Public Health Action

- Date: Monday, August 22, 2022

- Presenters:

- Rebecca Coyle, Executive Director, American Immunization Registry Association (AIRA)

- Kristy Westfall, Data Project Manager, Association of Immunization Managers

- Kate Ricker-Kiefert, Consultant, Civitas Networks for Health

- Elizabeth Ruebush, MPH, Senior Director, Public Health Data Modernization & Informatics, Association of State & Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO)

- Kathleen Tully, Public health analyst, HHS

- Paul Klintworth, Public Health Analyst, HHS/CDC/NCIRD/ISD/IISSB

- Overview: Leaders from various organizations and agencies involved in using and sharing immunization data provide information about their respective organizations, the work they are doing that is aligned with immunization data sharing and modernization, and their thoughts on being prepared for the next major public health event.

The Immunization (IZ) Gateway is a policy framework and cloud-based message routing system that supports data exchange among Immunization Information Systems (IIS), vaccine providers, and direct-to-consumer applications. Efforts are underway to enhance data that is submitted to the CDC on a monthly (flu) and quarterly basis (routine). Key to these submissions is a core technology known as privacy-preserving record linkage (PPRL), which facilitates analyzing data more efficiently for public health decision-making. The public is encouraged to participate in developing enhancements to immunization data and reporting.

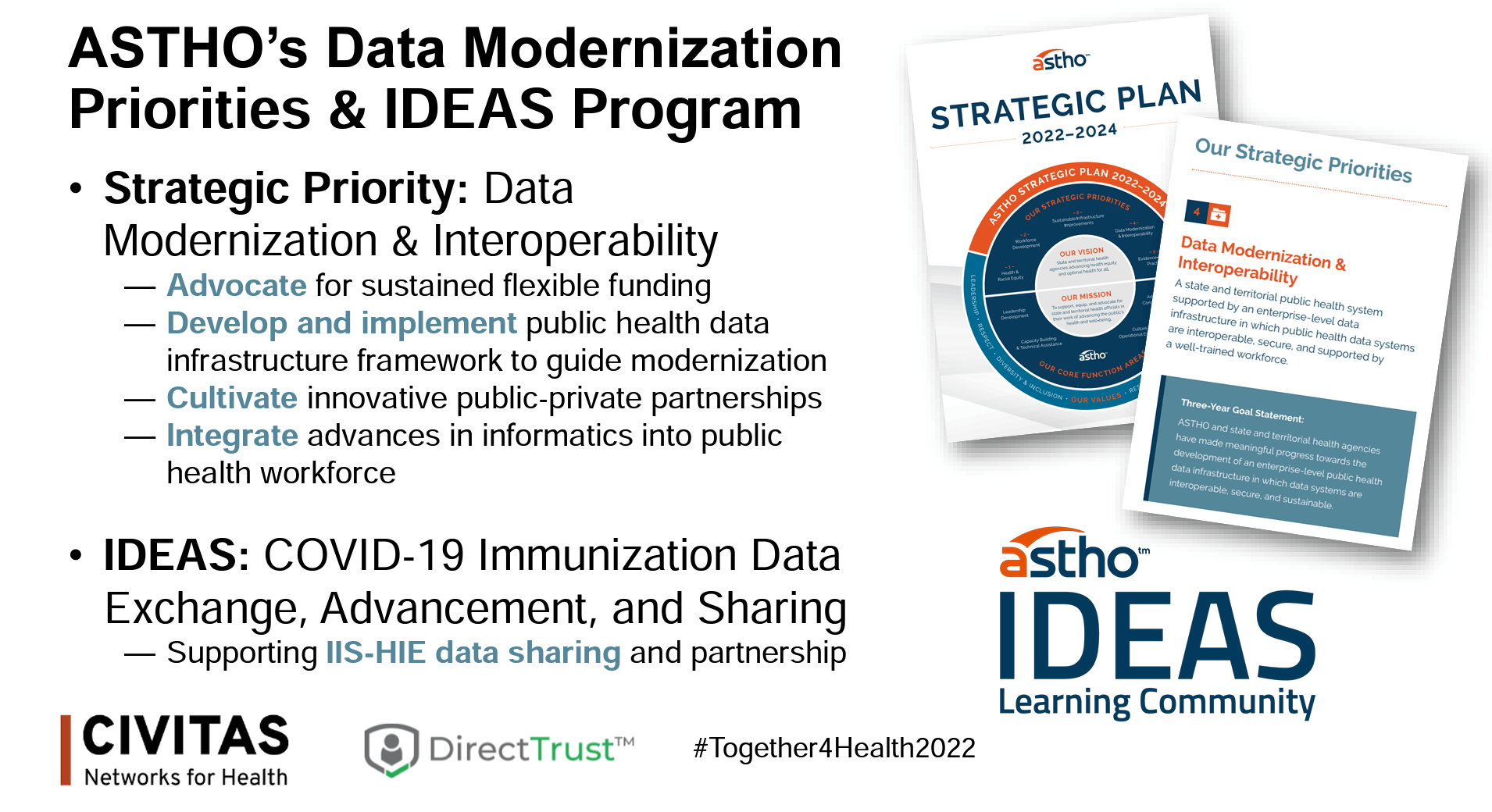

The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) is a national nonprofit organization representing public health agencies across the U.S. The organization is focused on data modernization and interoperability. Strategic priorities include:

- Advocating for sustained, flexible funding

- Developing and implementing a public health data infrastructure framework to guide modernization

- Cultivating innovative public-private partnership

- Integrating advances in informatics into the public health workforce

ASTHO is heavily involved in the ONC’s COVD-19 Immunization Data Exchange, Advancement, and Sharing (IDEAS) funding initiative, which supports IIS data sharing and partnerships with HIEs.

ASTHO is heavily involved in the ONC’s COVD-19 Immunization Data Exchange, Advancement, and Sharing (IDEAS) funding initiative, which supports IIS data sharing and partnerships with HIEs.

The Association of Immunization Managers (AIM) represents the 64 immunization programs that receive funding from CNC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD). AIM is dedicated to working with its partners across the country to:

- Reduce, eliminate, or eradicate vaccine-preventable diseases

- Promote the adequate and efficient allocation of resources to immunization efforts

- Promote the development and implementation of sound immunization policies and programs

- Provide a forum for effective information sharing and leadership development.

AIM is currently involved in the following:

- AIM IIS Advisory Group

- Medicaid-IIS Data Exchange MOU Project

- Immunization Integration Program (IIP) Executive Committee

- Reminder Recall services and resources (to increase vaccination participation)

- AIM Leadership in Action Conference (August 30-September 1, 2022, in Philadelphia, PA)

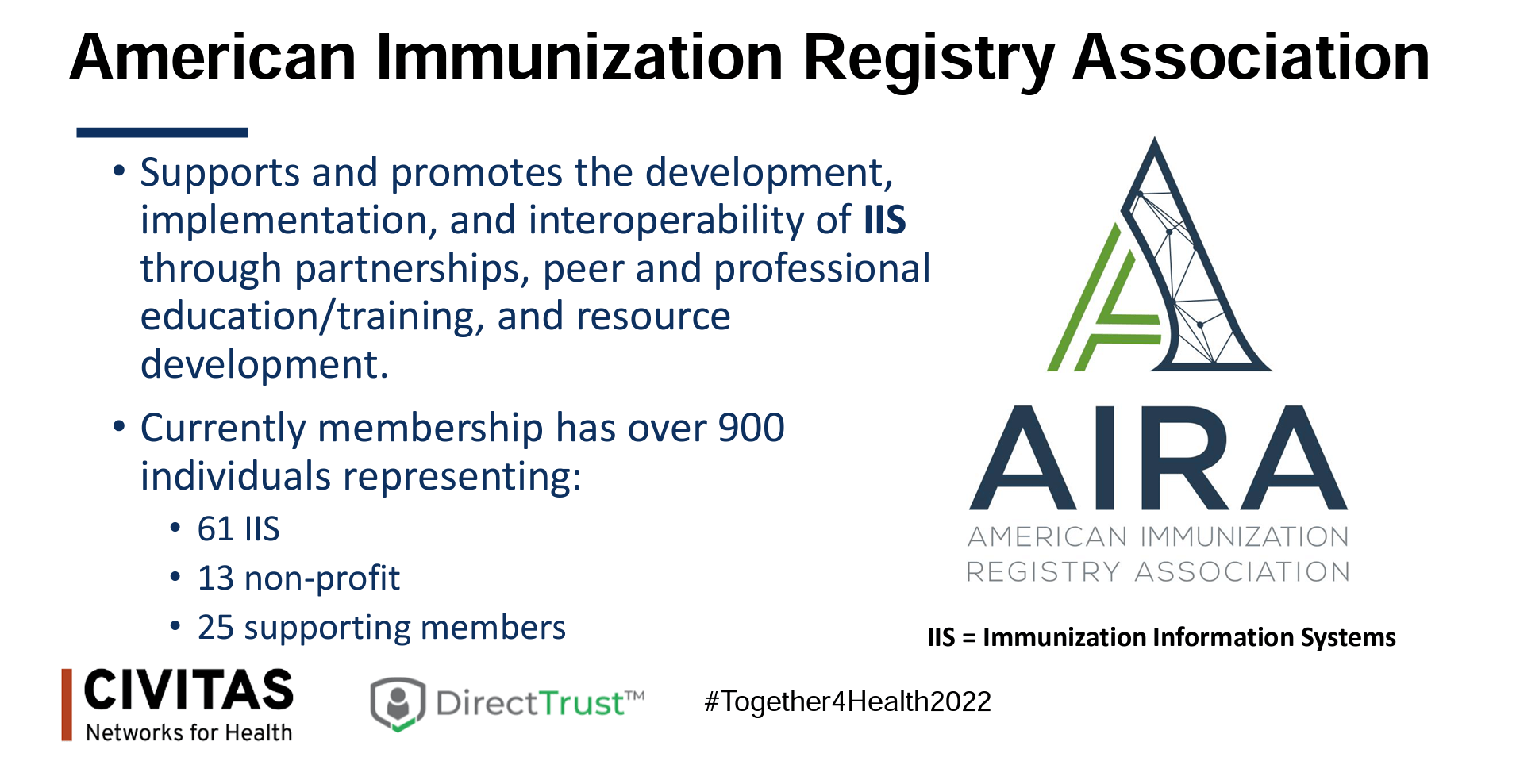

The American Immunization Registry Association (AIRA) supports and promotes the development, implementation, and interoperability of IIS through partnerships, peer and professional education and training, and resource development. Today, AIRA has over 900 members representing 61 IIS, 13 nonprofits, and 25 supporting members. The organization is working to improve data quality and modernize infrastructure, as well as is collaborating with the CDC to identify needs by jurisdiction and then identify and secure resources.

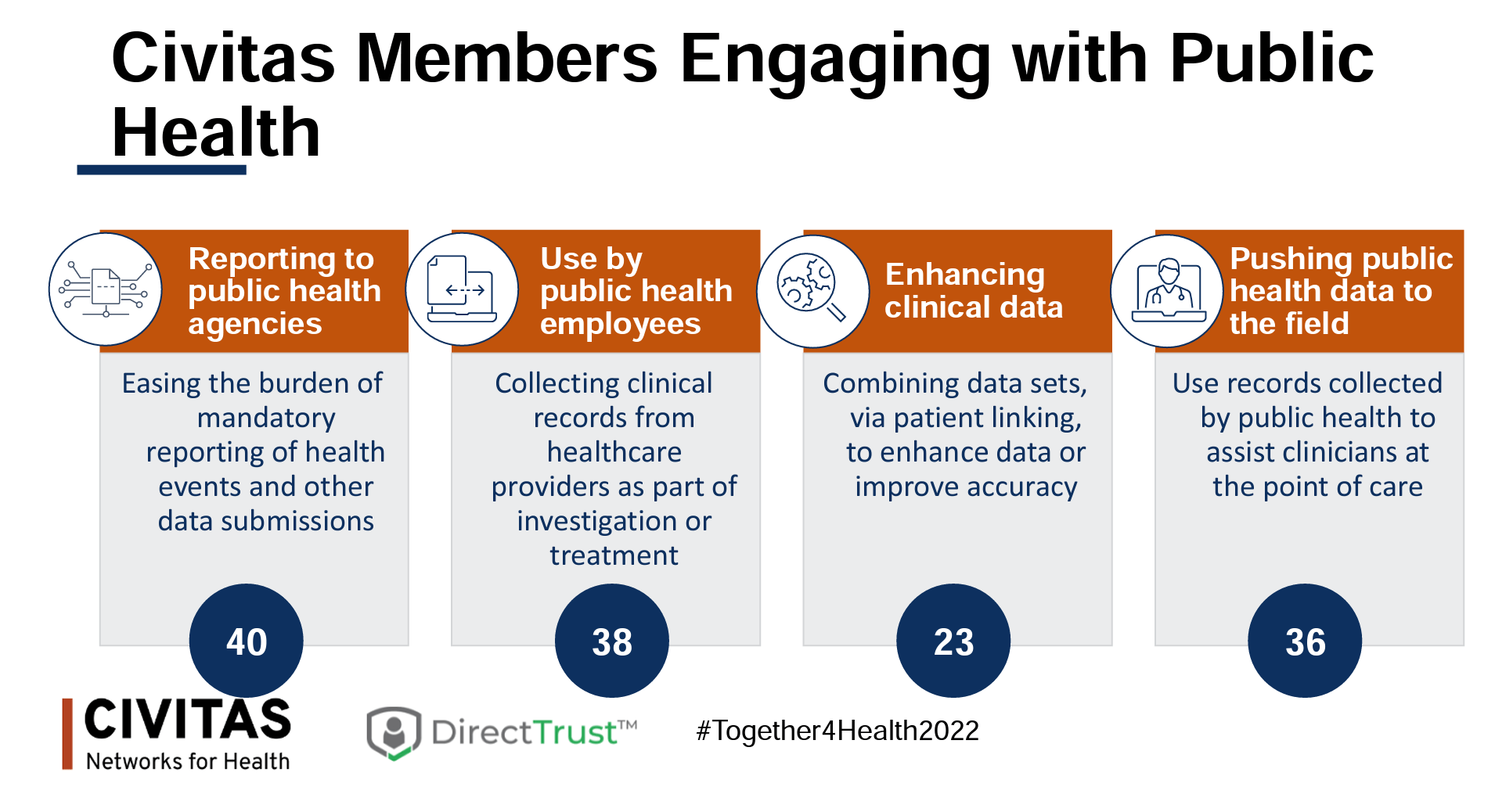

Civitas Networks for Health champions member involvement in collaborations specific to public health and reporting. Civitas and its members are:

Civitas Networks for Health champions member involvement in collaborations specific to public health and reporting. Civitas and its members are:

- Finding ways to ease the burden of mandatory reporting of health events and other data submissions

- Collecting critical records from healthcare providers as part of diagnosis investigation or treatment

- Combining data sets via patient linking to enhance data and improve accuracy

- Promoting the use of records collected by public health to assist clinicians at the point of care

Civitas is engaged in the following aligned activities:

- ONC IDEAS – IIS and HIE Technical Assistance

- ONC IDEAS – CSRI HHS Dashboard

- Immunization Integration Program (IIP) Executive Committee

- Implement Health Data Utility framework with Maryland Health Care Commission

- Government Relations and Advisory Council

Today’s presenters discussed key immunization data takeaways for the audience. Rebecca Coyle, executive director of AIRA, said that prior to COVID-19, some organizations had trouble prioritizing vaccine information collection and submission. She explained that we have since seen growth in new relationships and connections, and immunization data is really starting to flow. However, we are still learning, and the experiences of moving data all the way up to the federal level for public health decision-making are new. She stressed that we need to expand into doing the same for routine immunizations and see data showing the vaccines being used to get them to the communities that need them most.

Kristy Westfall from AIM noted that we should continue to remind ourselves that immunization infrastructure is still outdated. It takes a crisis to see what we do and do not have. There is an opportunity now to advance and connect systems. Fortunately, a foundation for immunization reporting and sharing was in place heading into COVID-19, but not all the data people needed was being collected or captured in ways that made it easy to work with at an aggregate level. Westfall stressed that we must set expectations about system limitations and more clearly define where HIEs and other organizations can provide assistance and fill gaps. While improvements are worked on, we need to keep IIS limitations in mind as plans are made for future public health emergencies that might affect us, like COVID-19.

Paul Klintworth from Health and Human Services believes that mandated reporting makes a significant difference for the CDC. The IZ Gateway allowed for some of that exchange. As one example of impact, Veteran Health Affairs now has an official national strategy for sharing information, which is a first. 57 of the 61 jurisdictions are currently participating in the IZ Gateway. There is more work to be done, but because we now have data moving, we can start to look at national coverage, equity, and distribution to see where support efforts need to focus.

In order to get to this point, special efforts were required. A new clearinghouse had to be created to accept data from states, which was then converted to usable information to be available through the CDC’s website. None of this would have been possible without new and rapidly developed collaborations. Future enhancements will depend on that same willingness to seek out and cultivate partnerships.

Kathleen Tully with the ONC’s Office of Technology, Standard Division, called attention to lingering gaps in standards for health IT and public health. At the moment, the emphasis remains on race, ethnicity, and gender identity. At the federal level, there is a push to make progress through USCDI, so Tully stressed that we should continue to watch for updates related to this. We have now had a chance to develop and use dashboards that ultimately roll up to the national level and have learned what kinds of basic data elements are needed but remain troublesome. This information has shed more light on the fact that regulation and actual implementation are different and that these gaps need to be closed to make data use at all levels more efficient.

The speakers responded to a few questions from conference attendees, noting that we continue to deal with constrained resources and out-of-date technology from an immunization data perspective. There is a comparatively small number of people working on this data, and the technology is sometimes 20 years old. The speakers stressed we need more focus and specific language on the policy side to clearly define collection and reporting and that we need to do this before the next major public health event, not during or after.

Bridging the Health Equity Divide with ADT Notifications

- Date: Monday, August 22, 2022

- Presenters:

- Lisa Nelson, MS, MBA, VP Business Development, Principal Informaticist, MaxMD

- Laura McCrary, EdD, CEO, KONZA

- Michael Cordeiro, Director, Interoperability Market & Product Strategy, MEDITECH

- Bill Howard, Principal, Audacious Inquiry

- Farah Saeed, Interoperability Sales and Business Development, eClinicalWorks

- Overview: This session focuses on examples of using the Direct Standard(™) to facilitate event notifications using ADT messages.

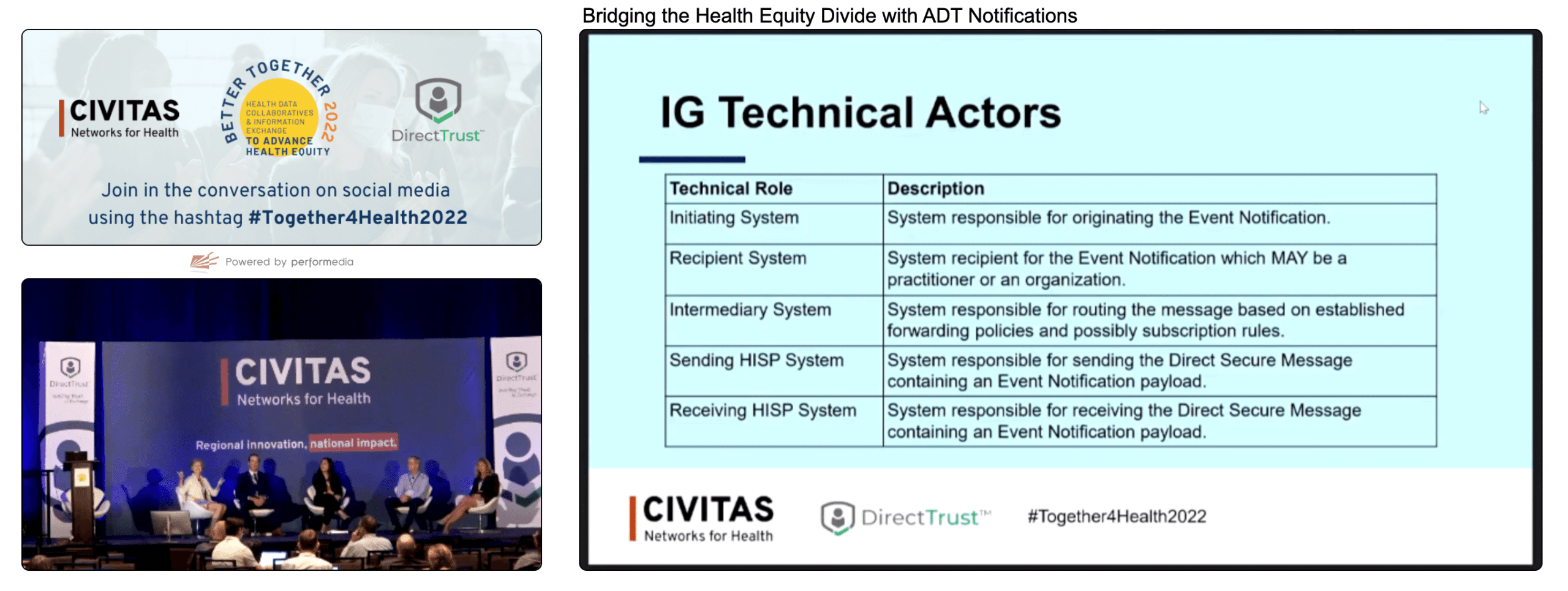

Lisa Nelson from MaxMD led today’s discussion. After brief introductions, Nelson provided a URL for information about the DirectTrust’s Event Notification via the Direct Standard (™) offering. An implementation guide (IG) is available, as well as an invitation to provide feedback to DirectTrust. The IG describes the following list of actors in an event notification (admission, discharge, transfer):

- Initiating System – Responsible for originating the event notification

- Recipient System – Responsible for receiving event notifications and might be a practitioner or an organization

- Intermediary System – Responsible for routing the message based on established forwarding policies and possibly subscription rules

- Sending HISP System – Responsible for sending the Direct Secure Message containing an event notification payload

- Receiving HISP System – Responsible for receiving the Direct Secure Message containing an event notification payload

The panel today represents most of these roles, including the following:

- Meditech – Initiating System

- Audacious Inquiry – Intermediary System

- MaxMD – Sending HISP System

- eClinicalWorks – Both Recipient System and Receiving HISP System

In order for Meditech’s ADT Notify solution to be widely adopted, it needs to occur within standard workflows. Direct was already used for discharge summaries, and extending the use of the standard for ADTs made the most sense. eClinicalWorks (eCW) and Audacious Inquiry (AI) were in similar situations. eCW wanted to take a proactive approach to comply with the Interoperability and Patient Access File Rule, so it was among the first organizations to approach DirectTrust about leveraging this technology for event notifications. AI had alerting services in 14 states and knew the final rule would have an important effect on their operations. One of the primary concerns was making sure that providing alerts would work for providers.

KHIN’s experience was different. At first, Dr. Laura McCrary did not pay much attention to the final rule’s impact because her organization already had a solution in place. However, McCrary found that their existing solution would not work for all of the practices that needed to receive notifications. Direct began to make more sense, and she heard from a growing number of organizations that they preferred to try to use this standard for ADTs. She was not entirely sure it would be successful, but due to the demand, she approved standing up a Direct-based solution for notifications. To her surprise, doing so only took about three weeks, and messages were received by the organizations that needed them. McCrary mentioned that many organizations already have a relationship with a HISP.

KHIN’s experience was different. At first, Dr. Laura McCrary did not pay much attention to the final rule’s impact because her organization already had a solution in place. However, McCrary found that their existing solution would not work for all of the practices that needed to receive notifications. Direct began to make more sense, and she heard from a growing number of organizations that they preferred to try to use this standard for ADTs. She was not entirely sure it would be successful, but due to the demand, she approved standing up a Direct-based solution for notifications. To her surprise, doing so only took about three weeks, and messages were received by the organizations that needed them. McCrary mentioned that many organizations already have a relationship with a HISP.

The panelists agreed that the publication of specifications in May helped make troubleshooting efforts more efficient and effective. Working to one code is far more productive. Most of the industry seemed ready for this kind of standard. As more organizations support the specification, integrations are expected to become more streamlined and less hands-on.

From Meditech’s perspective, the standard reduced development and deployment times. In many cases, end-users did not even know event notifications were being triggered because the solution was seamless, integrated into existing workflows, and worked behind the scenes as part of those workflows.

Now that more clarity exists and the industry has an option to leverage a widely used standard, organizations like eCW are building redesigned software such as their transitions of care module, knowing that these notifications are available. Search functionality now includes ADT information based on Direct event notifications. For AI, there is still work to be done to refine solutions and inbound data. AI has found, for example, that data elements like NPI are not always linked correctly, and it does not always make sense to have single provider attribution (sometimes it makes more sense to attribute to a panel, such as with the VA). They are making continuous improvements.

Meditech views ADTs as an opportunity to provide insight that some type of follow-up or further investigation is needed. We can begin to use ADTs to understand when patients have transportation issues or cannot afford medication and have had a flare-up of a certain condition. It’s important to think more about what factors led to a particular notification.

Meditech views ADTs as an opportunity to provide insight that some type of follow-up or further investigation is needed. We can begin to use ADTs to understand when patients have transportation issues or cannot afford medication and have had a flare-up of a certain condition. It’s important to think more about what factors led to a particular notification.

McCrary noted that it is the job of HIEs and QIOs to find value for customers, and ADTs, through a widely adopted standard, are of value to everyone involved.

The panel responded to a few attendees’ questions, including whether there is any adoption tracking now that Direct messaging is ANSI approved. While the panel did not have specific numbers, Scott Stuewe from DirectTrust contributed to the discussion and said that based on surveys, the overwhelming majority of respondents have said they are committed to developing and leveraging standards, including 8 of the top 10 EHR vendors.

Another attendee asked about ways to avert inappropriate admissions. The panelists agreed that many organizations are working on interventions upon arrival to avoid unnecessary admissions. The goal is to get patients to the proper level of care earlier in the patient flow. Using chief complaint information is often helpful in identifying opportunities to direct patients to more appropriate levels of care.

In terms of fees for developing and using the Direct Standard(™) for event notification, the panelists said that many organizations are already using ADTs, and many already have Direct for document exchange. Fees are likely nominal for organizations already using the standard.

Advancing Health Equity: Bridging the Gaps in Health Data and Measurement

- Date: Monday, August 22, 2022

- Presenters:

- Gregory Church, President, 4medica

- Jennifer D’Angelo, Sr Vice President, General Manager, New Jersey Innovation Institute

- Norm Thurston, Executive Director, National Association of Health Data Organizations

- Kyle Russell, MS, Chief Executive Officer, Virginia Health Information

- Paul McCormick, Vice President of Data, Center for Improving Value in Healthcare (CIVHC)

- Overview: A panel of leaders representing a cross-section of Civitas members introduce their respective organizations and discuss some of the benefits of state-designated HIEs (such as in New Jersey), as well as some of the ongoing challenges that still affect data collection, data quality, and the evolution of patient data over time.

This panel represented a cross-section of Civitas member types and was organized to share a broad range of perspectives.

This panel represented a cross-section of Civitas member types and was organized to share a broad range of perspectives.

4medica is a 24-year-old company working on aggregating thousands of data sources and dozens of data types into a single FHIR-based database. Their platform is intended to be a central solution for patients to view and share their information and includes a Global Healthcare ID. They aim to provide a foundation for health equity strategies based on their health data quality (HDQ) aggregated database of health records.

New Jersey Health Information Network (NJHIN) is the state-designated entity managing the HIE and is the only approved network to connect to public health registries. NJHIN supports the following key use cases: electronic case reporting (eCR), the Electronic Consent Management Registry (eConsent), Birth/Fetal Death Registry (EMS), consumer access, Electronic Practitioner Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (emPOLST), Active Care Relationship Service (ACRS), Consolidated Clinical Data Architecture (CCDA), Admission, Discharge, Transfer notifications (ADT), and the state’s Master Person Index (MPI).

The National Association of Health Data Organizations (NAHDO) is a nonprofit membership association and educational organization with members from the public sector, health care associations, corporate partners, and the general public. The focus of the organization is to promote the value of healthcare data. Health equity has been a focus area for NAHDO and its members, and the association hosted a health data equity event on August 25th of this year. NAHDO plans to host a conference in October 2022 to discuss data strategies and new data opportunities for identifying health inequities and how to supplement data for health equity studies.

Virginia Health Information (VHI) is a nonprofit that has been doing RHIC-type work since 1993. VHI took over the state’s HIE function in 2019. Recent highlights include the Emergency Department Care Coordination Program reducing super utilization of the ED by 25-30% (with Collective Medical), their all-payer claims database (APCD) is now pushing custom dashboards to over 1,100 practices for low-value care reduction as part of a multi-million dollar private grant, and they have been building our their Public Health Reporting Pathway (99% of relevant state reporting) in partnership with CRISP Shared Services. While not originally organized to address health equity topics, VHI has an inherent purpose of reducing health inequities.

The Center for Improving Value in Health Care (CIVHC) is a nonprofit organization serving as the administrator of Colorado’s APCD, which houses 870 million claims records from 36 commercial payers and Medicaid and Medicare, representing over five million lives.

The Center for Improving Value in Health Care (CIVHC) is a nonprofit organization serving as the administrator of Colorado’s APCD, which houses 870 million claims records from 36 commercial payers and Medicaid and Medicare, representing over five million lives.

The panel addressed a variety of questions during this session. Some key takeaways include:

- Precision and accuracy of individual person matching is one of the most important things we can do. We need to be able to understand and speak to the underlying trustworthiness of high-level data that we analyze, report, and use for decision-making. However, we also need to focus our analysis of data at an environmental level to detect structural issues or biases that we might not see at the individual level.

- NJ is in the process of mandating efforts to connect information across levels of care. Unfortunately, there is still a lot of faxing and time-intensive coordination.

- One of the most important changes over the last five or so years is in the past, we might identify data problems, but most would just keep going and assume we would fix the problems eventually. Today, however, we are far more likely to stop and fix the data as we go.

- In order for organizations to feel that they have usable information about disparities, they need complete and reliable information (which does not really exist today), an ability to find ways to tie data together from multiple sources, and confidence that when data is associated across databases, it is to the right person.

Certain kinds of data change over time. We need to account for this in data planning. For example, race data does not vary much at an individual level over time. However, gender identity and language can change for the same individual over time. To be accurate, it is important to work on understanding what leads to these changes. For example, is it because of different biases over time, fear, or true organic change? - States that require connectivity and interoperability might have an easier time responding to federal initiatives. In NJ, the focus is less on recruitment and more on educating providers and users on how to most effectively use the tools that are available.

- We need to pay attention to how data is collected. In some cases, we are in a rush, or the usefulness of data is not clear, and we pay less attention to data quality. Example: A community program for children receiving free breakfast used a process to capture participation information that relied on individuals “guessing” a child’s race and ethnicity as they walked in the door and recording it on paper forms as such.

- NJ is looking into interactive tools for their residents, such as portals, to enable them to interact with data and provide input. Additional time and energy will need to be spent working through difficult problems, such as when a patient makes an update in one portal, they might go to a provider’s office and still be asked to enter or fill in the same information again.

- Similarly, we need to improve our tools to enable providers to interact with data and make it more accurate and complete. For example, if claims data wrongly attribute a patient to a given provider, the provider needs simple and intuitive tools to help correct that information.

Thank you for joining us for Day One of Civitas! Stay tuned for more recaps!

| On Demand | Day One | Day Two | Day Three |

|---|