Summaries by Nathan Elliott. Formatting and editing by Madeline Rizzo

| On Demand | Day One | Day Two | Day Three |

|---|

Civitas Networks for Health is a national collaborative comprised of member organizations working to use health information exchange, health data, and multi-stakeholder, cross-sector approaches to improve health.

We’re in San Antonio this year for the Civitas Networks for Health 2022 Annual Conference. Join us over the upcoming days as we recap selected sessions from this year’s events! In this installment, we recap some of our favorite Day Three sessions.

Health Data Utilities: The Path to Effective Public Health Partnerships

- Date: Wednesday, August 24, 2022

- Presenters:

- Beth Anderson, MBA, President & CEO, VITL

- Neil Sarkar, Ph.D., MLIS, FACMI, CEO, Rhode Island Quality Institute

- Jaime Bland, DNP, RN, President and CEO, CyncHealth

- Overview: This session features insights into how HIEs with different funding models and state legislation put together the services and relationships needed to serve their communities as Heath Data Utilities (HDUs).

Jolie Ritzo, Senior Director of Network Engagement at Civitas Networks for Health, opened the session with some information about Civitas’ involvement in the concept of the Health Data Utility (HDU). The HDU model was featured at last year’s SHIEC conference and, since then, has been the focus of conversations with Civitas stakeholders, more than 50 congressional staffers, ONC, and other organizations and national Civitas partners. We are now at a point where we have emerging definitions and numerous use cases for HDU.

Over the past few days, we have been hearing about health equity infrastructure, which is an important function of the HDU model. Ritzo noted that achieving health equity means (as we heard in a previous session) putting health equity first.

Ritzo introduced the panel and turned the session over to Jaime Bland, President and CEO of CyncHealth in Nebraska. Bland’s organization has been adding services over the years toward functions as more of a utility, including PDMP in 2014, a community information exchange in 2018, and aggregating claims data. CyncHealth is now implementing its menu of services in Iowa.

Ritzo introduced the panel and turned the session over to Jaime Bland, President and CEO of CyncHealth in Nebraska. Bland’s organization has been adding services over the years toward functions as more of a utility, including PDMP in 2014, a community information exchange in 2018, and aggregating claims data. CyncHealth is now implementing its menu of services in Iowa.

Beth Anderson is President and CEO of Vermont Information Technology Leaders (VITL), the state’s designated operator of the Vermont Health Information Exchange (VHIE). Anderson said that VITL has been considered a public good since its inception and benefits from public funding, which is derived from a dedicated tax on health care claims. In 2017, VITL put in place a multi-stakeholder governance infrastructure, which includes representation from across the healthcare ecosystem in Vermont.

VITL has three primary goals:

- Creating one health record

- Informing and improving healthcare operations

- Informing investment and policy priorities

VITL has a growing relationship with Medicaid, having worked on services related to complex care management for Medicaid patients. VITL has also provided comparative analytics for Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH) participants and has calculated their payments. In addition, the organization has recently become certified as a module in the Medicaid Enterprise Systems (MES) marketplace. VITL is currently reviewing opportunities in prior authorization, supporting HEDIS reporting, and potentially serving as a data warehouse for MES reporting and analytics.

In addition to sharing some of the same successes during the COVID-19 that other HIEs have discussed at recent conference sessions, VITL learned that having state public health employees experience HIE data in a hands-on way for the first time has opened doors to collaborations and strategic alignment. VITL is now working on a strategic plan with the state’s public health department and is working on a bidirectional integration between VHIE and the immunization registry for providers to better serve their patients and communities.

In addition to sharing some of the same successes during the COVID-19 that other HIEs have discussed at recent conference sessions, VITL learned that having state public health employees experience HIE data in a hands-on way for the first time has opened doors to collaborations and strategic alignment. VITL is now working on a strategic plan with the state’s public health department and is working on a bidirectional integration between VHIE and the immunization registry for providers to better serve their patients and communities.

Rhode Island Quality Institute (RIQI) President and CEO Neil Sarkar described RIQI as the state’s longitudinal health record. Rhode Island has been an opt-in state, so RIQI has had to engage patients and providers differently than others. They have always needed a more direct campaign and engagement strategy. One of their primary tools has been a patient portal.

Sarkar told the story of being in a hospital for his own care and waiting for lab results to come back to show whether he was making progress in his recovery from sepsis. He was able to use the portal to check his labs before his care team had time to visit him and tell him in person. Sarkar believes it is increasingly important for patients to understand the value of taking direct action and ownership of their care and the information that informs it.

In addition to patient engagement, RIQI has also responded to provider requests. As one example, during the pandemic, RIQI produced information products for the state, including a dashboard. Providers also wanted to have access to this information, so RIQI began expanding the audience for the dashboard. That audience now also includes Medicaid accountable entities.

Sarkar believes that utilities need standards of quality and availability, just like water and electricity. He believes that SMART on FHIR has tremendous potential to help move his organization toward a utility. Sarkar described an example of implementing an off-the-shelf app into RIQI’s clinical viewer to help better organize data for providers and introduce it within existing workflows.

Sarkar believes that utilities need standards of quality and availability, just like water and electricity. He believes that SMART on FHIR has tremendous potential to help move his organization toward a utility. Sarkar described an example of implementing an off-the-shelf app into RIQI’s clinical viewer to help better organize data for providers and introduce it within existing workflows.

As tools like this one become more available and more widely used, Sarkar believes that more providers and payers will be motivated to spread the word in communities about the availability of HIE data.

RIQI is currently working on collecting stories from across the state. The HIE is using funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to hire community workers to engage with patients in communities to learn what they really need. Sarkar feels that data is essential, but so is talking to people to hear about needs directly from the source. Patients are, after all, the “secret sauce” of healthcare.

Sarkar also stated that, at least in New England, 70% of people stay close to where they are born. They don’t tend to leave, meaning their care and associated data tend to remain within borders. There are, however, exceptions. One of the most significant for Sarkar is specialty care and the extent to which people do travel for non-routine care.

Bland takes a slightly different view. In her experience in the midwest, people travel a lot. Whether for vacation or for care, people and data tend to move frequently. For areas like this, the goal of HDUs will be to solve the “wouldn’t it have been nice to know?” problem for providers, in particular. Provider needs are central to CyncHealth’s work.

Bland also commented on the differences between urban and rural needs. She feels that urban areas tend to get more attention, but rural areas have some of the most pressing needs. In some cases, facilities do not have an IT resource for more than one day per month, so meeting data needs and getting those organizations fully connected is especially challenging and can take a long time.

Sarkar sees similar challenges compressed into a very small geographic area. A short drive in Rhode Island will show you the extremes of affluence and poverty. In order to help those in need, RIQI has been working directly with community organizations like food pantries (or food banks) to educate community members about food choices as it relates to their health and available information. The effort here is to help teach patients to take ownership of their care. The burden to remember important life influences or medications tends to fall on patients, and providers simply are not aware of what goes on for a patient in other settings. This lack of awareness is where HDUs need to be a resource in their communities.

Anderson said that Vermont also has rural challenges and has fewer than 700,000 residents in the state. It is important in a state like Vermont for providers to know whether patients are truly getting all of their care nearby (which is what many in Vermont assume) or are going elsewhere and for which services.

The session moved to a Q&A session.

Q: Do the partner organizations in New England have a common infrastructure?

Sarkar answered that their technologies are different, and they see value in this. Rhode Island, Vermont, and Maine’s partnership means sharing ideas and examples of what is working, and the others can then go back to their respective vendors to request enhancements and new tools that add value for everyone. The partnership establishes a type of learning organization or network that helps all parties improve.

Q: What are some “gold star” use cases in the HDU model?

Bland suggested contract tracing as one example, which leverages the master patient index (MPI), demographics as a service, event notification, following a person through treatment, readmission, long COVID, and offering a more complete basis for public health insight over time.

Sarkar felt that a great example in his state is working with accountable entities to identify populations that would benefit from multi-specialty care before they show up at a hospital. In other words, using HDU data and tools to advance preventive outreach, intervention, navigation, and care before patients’ health deteriorates to the point of needing higher levels and more expensive care.

Q: When we think about utilities, we often assume they are doing their best work when no one notices them. How do we reconcile that thinking with the need to demonstrate value to stakeholders?

Sarkar feels that we have a lot to learn from utilities. While they are sometimes thought to be invisible, people are upset as soon as they are unavailable when you need them (internet, power, etc.,). What utilities do, though, is offer services that help customers make better plans to avoid or be ready for disruptions. For example, utilities offer maps where customers can see outages and resolution efforts in near real-time, and they sometimes include information about upcoming weather that might disrupt services. There is still much to be learned and resolved, but we should look at how other utilities have proven their worth and value over time.

From Bland’s perspective, it’s not as much about community outreach. Instead, it’s more about making sure that stakeholder CEOs are aware of what is available and how it can benefit their organizations. Bland believes that the priority should be on resolving policy issues that discourage data flow and result in duplicating services and waste.

Q: How much does private funding play a role, and what is the value proposition for private funders?

VITL and CyncHealth are largely state-funded, but VITL is looking to change their model and is actively involved in exploring partnership opportunities in the community where fee-based services would be supported. RIQI relies heavily on private contributions and must go to the community to ask for financial support each year. RIQI is now beginning to move from what was viewed as an experiment to an essential service that people depend on, so funding becomes important, but the value proposition is increasingly clear for many. RIQI also offers “boutique analytics” and receives revenue from certain alerts and tracking tools.

Q: How did Rhode Island work with its population to help them understand that patient access is possible? What were some of the challenges as they onboarded? What should other HIEs expect?

As an opt-in state, RIQI spent a lot of time directly interfacing with the community to build trust and encourage participation in the HIE. Since launching the portal, there has been a lot of need to support things like password resets and other helpdesk issues. Rhode Island is shifting to an opt-out model, and there are plans to engage patients during their care to encourage the use of the portal. It’s very important for patients to understand what is going on with their care. It cannot be the CEO or staff driving patient understanding. It has to be peers, neighbors, and family members explaining the value of having access to their health records as part of managing their care.

Q: What different types of organizations are represented in the HDU model?

Bland said that CyncHealth has HIE functions, prescription monitoring, all-payer claims data, community information exchange, health collaboratives with researchers and academia, and a foundation working on topics like the long-term effects of mold remediation. In addition to care services, an HDU will need legal and advocacy divisions. CyncHealth has four separate 501 (c)(3)s, and Bland believes it takes this kind of corporate structure to keep everything manageable.

Sarker and Anderson both described the need to partner with a broad set of outside organizations to help break down silos of data. As Anderson put it, developing partnerships is key to the HDU model.

Improving Health Equity Through Social Needs Tools: HIEs and Community Providers Innovating to Share Data and Address Both Medical and Social Needs

- Date: Wednesday, August 24, 2022

- Presenters:

- Jessica Nadler, Managing Director, Deloitte Consulting

- Craig Jones, MD, Chief Medical Officer, Idaho Health Data Exchange

- Deniz Soyer, Project Manager, DC Department of Health Care Finance

- David Kendrick, MD, MPH, MD, MPH, FACP, CEO, MyHealth Access Network

- Rachel Thomas, Senior Director of Customer Success, findhelp

- Overview: Experts from HIEs in Idaho, Oklahoma, and Washington, DC, talk about their organizations’ evolution into focusing on social needs data, how they approach defining priorities for social needs offerings, and what’s next for each.

Jessica Nadler from Deloitte began the session by providing Deloitte’s working definition of equity: “The fair and just opportunity for every individual to achieve their full potential in all aspects of health and wellbeing.” Nadler also likes the somewhat more concrete: “Equality is when everyone has a pair of shoes, but equity is when everyone has a pair of shoes that fit.”

Deniz Soyer from the DC Department of Health Care Finance introduced a public/private collaboration between the Department of Health Care Finance, CRISP DC (HIE), the DC Primary Care Association, and the DC Hospital Association, known as the Community Resource Information Exchange (CoRIE). The intent of CoRIE is to support a vendor-agnostic solution for whole person care. CoRIE provides the following:

Deniz Soyer from the DC Department of Health Care Finance introduced a public/private collaboration between the Department of Health Care Finance, CRISP DC (HIE), the DC Primary Care Association, and the DC Hospital Association, known as the Community Resource Information Exchange (CoRIE). The intent of CoRIE is to support a vendor-agnostic solution for whole person care. CoRIE provides the following:

- Screening for social risks

- Resource lookups

- Referrals to appropriate community and social services

David Kendrick is an internal medicine physician representing MyHealth Access Network, the state-designated HIE in Oklahoma formed in 2009. Kendrick studied engineering prior to medicine and always knew that you “can’t fix what you don’t measure.” This statement means starting with data and actually measuring solutions and improving them over time.

Since 2015-2016, we’ve had the CMMI’s Accountable Health Communities. MyHealth Access Network sought to participate, but after the award, found that the required 15-question survey took longer than expected to complete and added some degree of burden. They asked to alter the approach by using ADTs. Fortunately, this suggestion was accepted. The new model sent a text message when a patient registered. Intake staff would tell patients that if they received a text, the doctor really needed them to respond. On mobile devices, the new assessment tool took 3-4 minutes to fill out. The original form took 12-13 minutes. Submissions were then scored, and tailored results were delivered back to the patient while they were still in the waiting room. They could then click a link in a text message to set up appointments with community resources that could help with specified needs.

Since 2015-2016, we’ve had the CMMI’s Accountable Health Communities. MyHealth Access Network sought to participate, but after the award, found that the required 15-question survey took longer than expected to complete and added some degree of burden. They asked to alter the approach by using ADTs. Fortunately, this suggestion was accepted. The new model sent a text message when a patient registered. Intake staff would tell patients that if they received a text, the doctor really needed them to respond. On mobile devices, the new assessment tool took 3-4 minutes to fill out. The original form took 12-13 minutes. Submissions were then scored, and tailored results were delivered back to the patient while they were still in the waiting room. They could then click a link in a text message to set up appointments with community resources that could help with specified needs.

Kendrick acknowledged that it took a while to build this solution. It needed to be vendor-agnostic, and there were many requirements to meet because this was considered a research project. MyHealth had already convened community-level governance, and input from that structure asked if MyHealth should offer this for everyone, not just Medicare/Medicaid patients. The assessment and referral solution has now been used by over 3 million people and has continued through COVID-19. Kendrick said that the tool has led to hundreds of thousands of social needs being met. Interestingly, they also found that the commercially insured have a much higher than expected need rate.

MyHealth Access Network is expanding on this infrastructure with the goal of adding more information while routing results back to practices to include in patients’ plan of care without burdening providers.

Craig Jones from Capital Health Associates worked with the state of Idaho just before COVID-19 to start restructuring its health information exchange. They worked through identity management and talked with many stakeholders to gather input. One of the things they found was the need to go beyond traditional healthcare and bridge gaps with social support services. They began looking at different HIE platforms to support this and ended up selecting findhelp.org as an add-on to their existing platform.

The addition of findhelp.org sparked a lot of interest from community resources and EMS as they interacted with people in the community. People can go to the findhelp.org tool to get social needs information, initiate referrals, and share information with community-based organizations (CBOs) to begin a closed loop referral process.

The addition of findhelp.org sparked a lot of interest from community resources and EMS as they interacted with people in the community. People can go to the findhelp.org tool to get social needs information, initiate referrals, and share information with community-based organizations (CBOs) to begin a closed loop referral process.

There was so much interest in this that a collaborative was formed to address social needs. The platform is public-facing, so CBOs, residents, United Way, and others can use it as needed. The next phase is tighter integration with the HIE so that social needs data can be brought into the data warehouse and linked with clinical data for more uses, including population health models for the state.

Rachel Thomas provided a brief overview of findhelp.org and talked about how the organization’s CEO started the findhelp.org journey as a result of frustrations and confusion navigating his own family’s health crisis. Even though Thomas and her husband both work in healthcare, they have struggled to navigate the industry for their own healthcare needs. If professionals working in the field are challenged by finding their way to the resources they need, just imagine what it is like for people who do not.

Rachel Thomas provided a brief overview of findhelp.org and talked about how the organization’s CEO started the findhelp.org journey as a result of frustrations and confusion navigating his own family’s health crisis. Even though Thomas and her husband both work in healthcare, they have struggled to navigate the industry for their own healthcare needs. If professionals working in the field are challenged by finding their way to the resources they need, just imagine what it is like for people who do not.

The panel moved to a Q&A session.

Q: How are you handling governance and funding?

Kendrick talked about community-level governance and how his organization has had to rely on that governance structure for many things. An example includes transitioning from an AHC model to ongoing formal governance and dealing with problems like avoiding putting referrals on phones for patients in domestic abuse situations where the abuser could see the message. Originally funding was tied to research, so it came with many constraints. Now that these solutions are up and running, MyHealth needs to find funding to keep them going.

Soyer explained that the DC Department of Health Care Finance and its initiatives like CoRIE operate like a Health Data Utility. They foster a culture of shared responsibility across entities. Funding comes from the local council, and they have leveraged HITECH funding. DC was the first jurisdiction to leverage this funding for SDOH. They are now pivoting to relying more on funding associated with sister agencies as value is added and demonstrated.

According to Jones, Idaho designed an intensive approach to stakeholder engagement by building a collaborative with hundreds of CBOs. Meetings include payers and providers and other types of organizations and feature the sharing of many stories and examples. Unfortunately, the state did not want to consider supporting all of us as a utility after federal money ended. The HIE is working on a revenue model supported primarily by participants.

Thomas mentioned that some organizations tend to try to lead with technology first. Models like this can take years to build and still not find value. Ultimately, organizations need to identify their “north star,” stay focused on that and reach out and learn from others.

Q: What are you most excited about in the next twelve months?

Soyer said that people are increasingly using the tools that are available. The focus is going to be on using the tools well and consistently. Additionally, Soyer’s organization will be working on population health analytics and pulling in SDOH data.

Kendrick talked about a mandate that passed in Oklahoma for providers to connect to, send to, and use the HIE. There are also expanded requirements for capturing social data, and MyHealth will be working to consolidate the multiple existing closed loop referral solutions in a vendor-agnostic way. Oklahoma’s crowdsourced inventory of community resources will continue to grow, and one of the things Kendick is most excited about as a clinician is having community resource information paired with both clinical information and claims data in one place.

Jones said that Idaho is looking at how to use clinical data with SDOH data combined with other public data such as the Area Deprivation Index (ADI). Jones also looks forward to better coordination between not only primary care and social services but also specialty care as well.

Thomas said that so many organizations are on the brink of having robust longitudinal records and tools to reduce the burden on providers. She is excited that many more organizations will arrive at this destination in the next year.

Q: What are your thoughts on handling relationships with providers and information flows with the expected convergence of NCQA, value-based models, and social needs screening?

Idaho has taken an assertive approach in working with payers. Jones said that their goal is to improve their response to meeting payers’ needs and attempt to be a single point of contact to address payers’ current and future data sharing requirements. Meeting those needs means payers become more interested in investing in HIEs. Payers are critical stakeholders.

Kendrick added that payer relationships are very important to sustaining HIEs, but providers have to be the ones to use the data and the tools to directly change care and outcomes.

Addressing Health Equity Through SDOH Data Sharing & Collaborative Efforts Across Texas

- Date: Wednesday, August 24, 2022

- Presenters:

- Heidi McPherson, MPH, Sr. Project Manager, University of Texas Health Science Center – SPH

- Seydia Adkins, MA, Public Health Program Liaison, City of Lubbock Health Department

- Eliel Oliveira, Director, Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin

- Overview: Community health leaders in Texas discuss the tools and techniques they are using to promote the use of SDOH data at the community and state levels.

Eliel Oliveria, director of research and innovation at Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin began the session.

Oliveira posed the following key question:

Oliveira posed the following key question:

“What is the demonstrated need for systems to change to promote health equity in our communities?”

These essential needs are:

- Community engagement and building coalitions with individuals, community organizations, industry, and government.

- Governance that is not recreating community resources.

- Technical infrastructure through standards and strategy technical assets

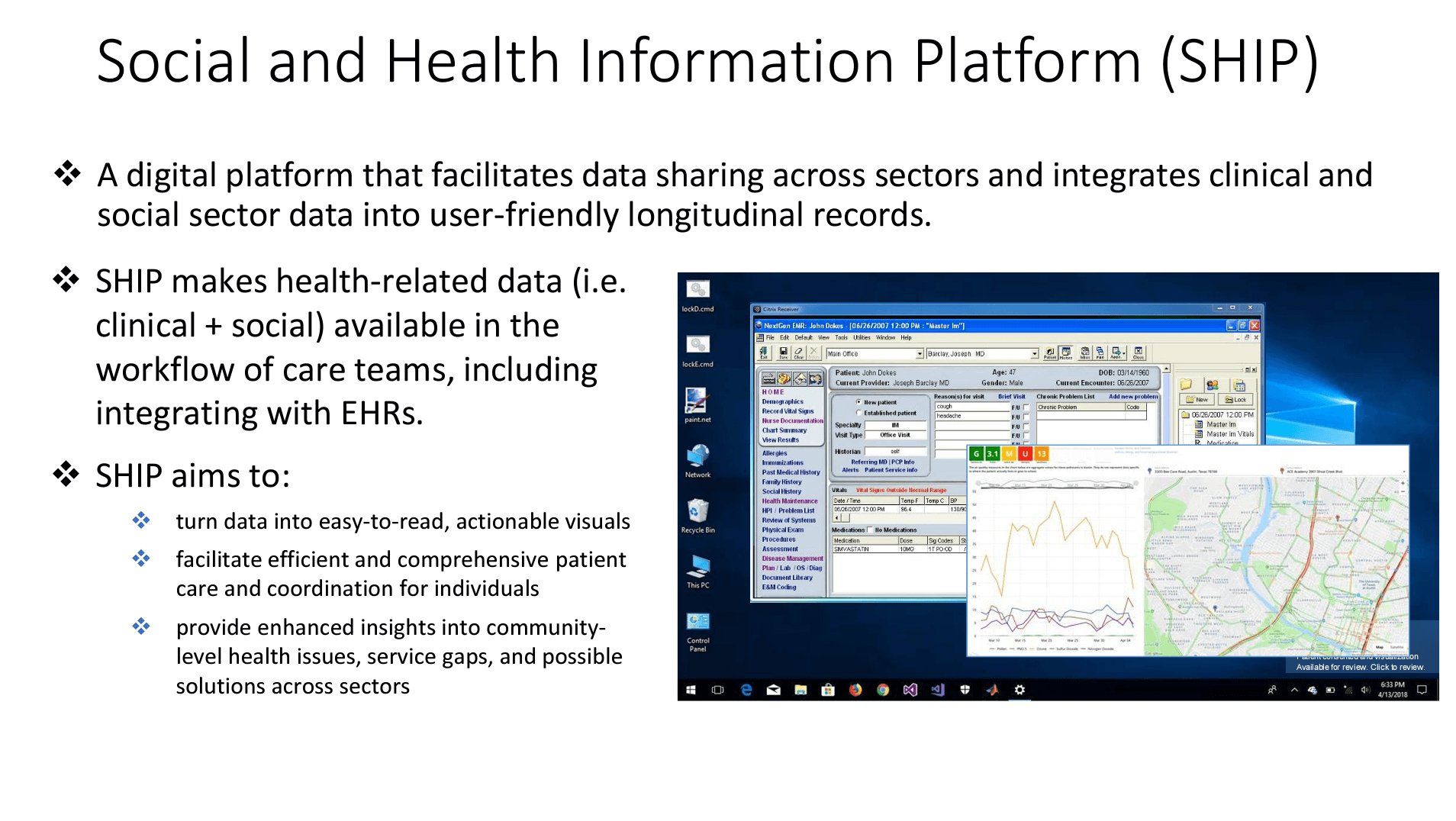

In response to these, the Social and Health Information Platform (SHIP) was launched as a digital platform that facilitates data sharing across sectors and integrates clinical and social sector data into user-friendly longitudinal records. SHIP makes health-related data available in the workflow for care teams, including integrating into EHRs. Data can come from any source, such as homelessness or prison data. Both clinical and community based organization staff can access the platform.

In response to these, the Social and Health Information Platform (SHIP) was launched as a digital platform that facilitates data sharing across sectors and integrates clinical and social sector data into user-friendly longitudinal records. SHIP makes health-related data available in the workflow for care teams, including integrating into EHRs. Data can come from any source, such as homelessness or prison data. Both clinical and community based organization staff can access the platform.

The solution monitors data traffic and alerts a clinician for the next action. Oliveira shared a slide showing a sample pediatric asthma dashboard that had information about local data. This information included weather data, sensor data, school data, neighborhood data, and data on a patient’s proximity to risk factors or services, all of which give clinicians a sense of the challenges a patient might be experiencing at the time of the visit. SHIP currently uses and connects SDOH data from PRAPARE, social services information through findhelp.org, and clinical information through the HIE (Connxus).

SHIP provides worklists for Community Health Workers (CHWs) to complete SDOH assessments for individuals without a current assessment, placing referrals for identified SDOH needs and updating the status of those for whom referrals are made. Oliveira shared another view of patient-level summaries, which display past SDOH survey results from multiple organizations and lists previous referral information.

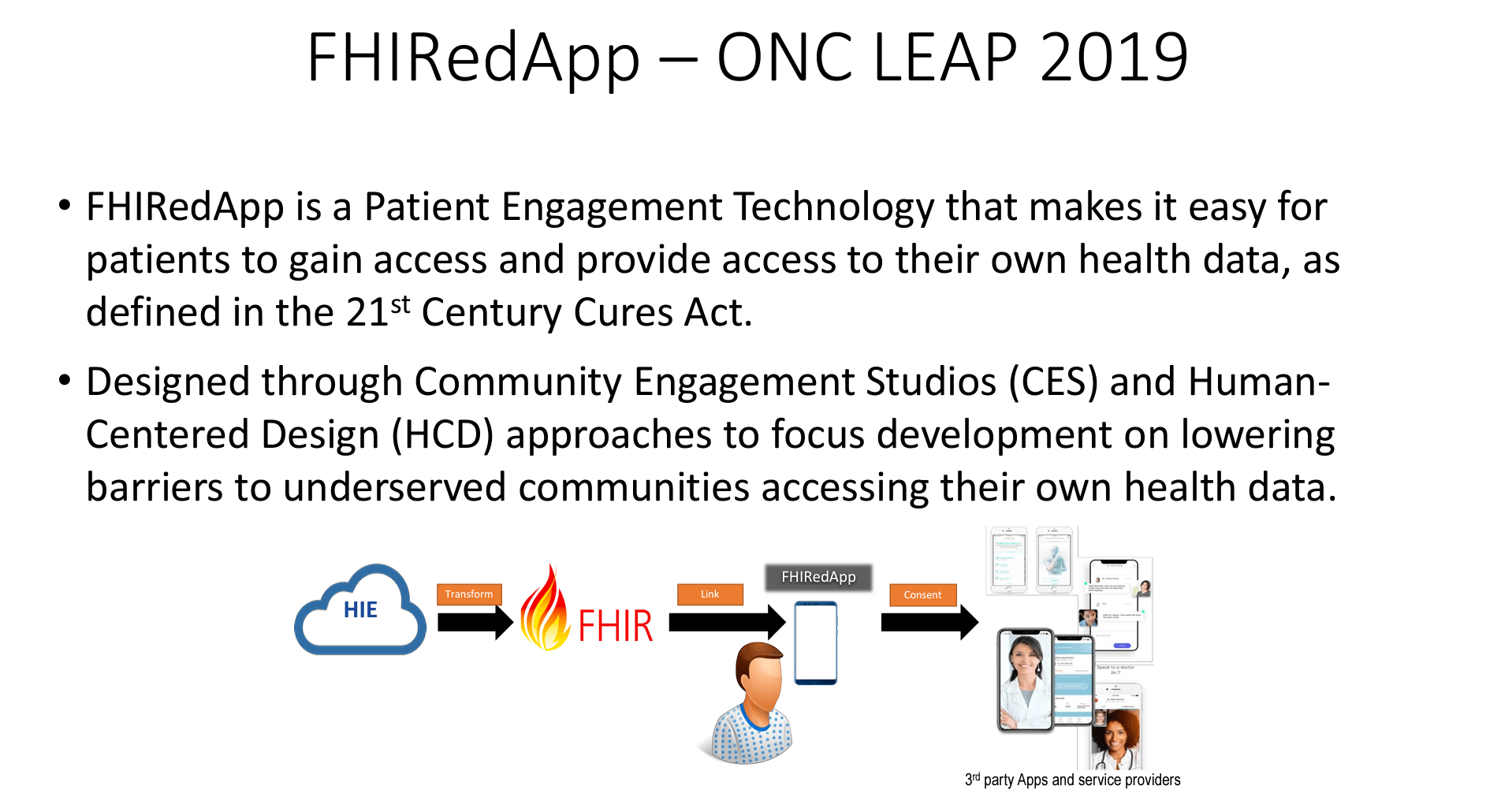

SHIP is now being linked to a previously developed mobile app that allows patients to access their data. FHIRedApp (“fired app”) was developed using ONC LEAP funding in 2019. It is a patient engagement technology that makes it easy for patients to gain and provide access to their health data, as defined in the 21st Century Cures Act. It was designed through Community Engagement Studios (CES) and Human-Centered Design (HCD) approaches to focus development on reducing barriers to underserved communities. The goal is to continue to enable improved data access and use through an ecosystem of API-based solutions based on the FHIR standard.

SHIP is now being linked to a previously developed mobile app that allows patients to access their data. FHIRedApp (“fired app”) was developed using ONC LEAP funding in 2019. It is a patient engagement technology that makes it easy for patients to gain and provide access to their health data, as defined in the 21st Century Cures Act. It was designed through Community Engagement Studios (CES) and Human-Centered Design (HCD) approaches to focus development on reducing barriers to underserved communities. The goal is to continue to enable improved data access and use through an ecosystem of API-based solutions based on the FHIR standard.

The Central Texas Food Bank (CTFB) is using this platform today. They receive a referral from a clinical provider, and the patient is notified. When accepted, a patient answers a small number of eligibility questions and then is scheduled to meet with food bank staff (translators are provided, if needed). The patient receives another link to upload documents or photos of documents that the food bank uses during the application process. Follow-up texts are sent to determine whether the patient has received their letter from Medicaid and if denied, staff work to close the loop with the patient. The platform allows staff to see where people are in the process, and outreach calls can be made to patients if they do not complete the questions or have other concerns that stall the process. So far, 30% of these referrals get closed. The remainder are not, but efforts are underway to reduce these.

McPherson and Adkins took turns presenting information about community-wide efforts to address SDOH. Adkins discussed the City of Lubbock’s Health Department and the efforts to run a program called LBK Community. Having the city involved in an SDOH initiative provides credibility and helps to accelerate improvements. Politics can play a role, but stakeholders work to maintain strong relationships with all parties involved over time.

McPherson and Adkins took turns presenting information about community-wide efforts to address SDOH. Adkins discussed the City of Lubbock’s Health Department and the efforts to run a program called LBK Community. Having the city involved in an SDOH initiative provides credibility and helps to accelerate improvements. Politics can play a role, but stakeholders work to maintain strong relationships with all parties involved over time.

The program has 31 partners, 78 staff programs, and over 260 registered users. As of August 15th this year, LBK Community has 427 contacts and 734 needs identified, with 73% of referrals closed. The most frequent needs are food insecurity, case management, utilities, medical assistance, and housing.

Partners are using LBK Community’s platform in ways that are unique to their respective workflows. In some cases, hospitals use it to screen for social needs during the admissions process, while others use it for active case management. LBK Community seeks to influence health equity by stabilizing non-medical drivers of health. The collection and use of SDOH data led to collaborative meetings focusing on topics such as access to dental care.

The Health Equity Collective represents about 180 organizational members and 500 individuals (many with lived experiences who can inform how systems need to evolve) who are working together for care coordination and to address non-medical drivers of health. The Health Equity Collective has eight work groups focused on establishing common definitions.

The Health Equity Collective’s framework produced the following primary goals for systems change:

- Technology capacity

- Services access for all

- Ease of referrals and care coordination

- Human capacity

- Facilitation of CHW Network for the Greater Houston area, workforce development, employer engagement, and community information exchange access

- Community voice

- Building of engagement strategies to inform the community information exchange

- Community voice to inform policy

These goals led to the following priority outcomes:

- Improved SDOH care

- Improved food security

- Improved mental health

The Texas SDOH Workgroup is a learning collaborative focused on health equity, wellness, and growth. It is composed of forward thinkers and those who are systems and policy-minded. Members share a lot of pride in their Texas roots. There are several efforts across Texas to address SDOH, but not a comprehensive effort to bring communities together to address these needs.

Oliveira concluded the session with responses to the following:

“How do we sustain and pay for these systems changes? Is this population health infrastructure?

Oliveira sees the answer as a combination of building use cases one at a time to prove impact and outcomes, along with having consistent, substantial, and accountable public funding. Ultimately, we need local examples of success that are amplified by providers, organizations, and communities coming together to tell their stories to the state.

Call to Action/Adjourn

- Date: Wednesday, August 24, 2022

- Presenters:

- Lisa Bari, MBA, MPH, CEO, Civitas Networks for Health

- Scott Stuewe, President and CEO, DirectTrust

- Overview: Lisa Bari from Civitas and Scott Stuewe from DirectTrust offer their thanks to conference attendees, sponsors, and vendors for making this year’s conference a success.

Lisa Bari thanked everyone for their engagement and participation in this year’s conference. She called attention to the many hallway conversations and discussions within sessions, stating that we must continue to work to tell our stories in any way we can. People need to hear and visualize examples of what we are doing in the real world.

Scott Stuewe concluded by celebrating the opportunities for people to create new ideas at this conference, sitting in corners between sessions and forming new synergies or working through problems together. While this collaboration between Civitas and DirectTrust has been a first, Stuewe sees no reason to think we will not continue to combine efforts in the future.

Two reminders:

- Civitas board elections are open.

- Think about the mix of organizations and knowledge that you want to have represented at Civitas in the future and provide your feedback.

| On Demand | Day One | Day Two | Day Three |

|---|

Thank you for joining us for Day Three of Civitas. We look forward to next year’s conference!

J2 Interactive is an award-winning software development and IT consulting firm specializing in customized solutions for hospitals, labs, research institutions, and health information exchanges.

Our approach to design and development is rooted in a fundamental belief that systems succeed or fail based on how well they serve the people who depend upon them. Drop us a line to learn more.